TL;DR: On October 28, 2025, the National Executive Board removed chartered organizations as automatic voting members of local councils. That matters because chartered organizations were the Scouting movement’s formal pathway into governance, even if that pathway was often unused. With it gone, BSA’s governance becomes even more self-selecting, more insulated, and more vulnerable to capture by commissioned bureaucrats.

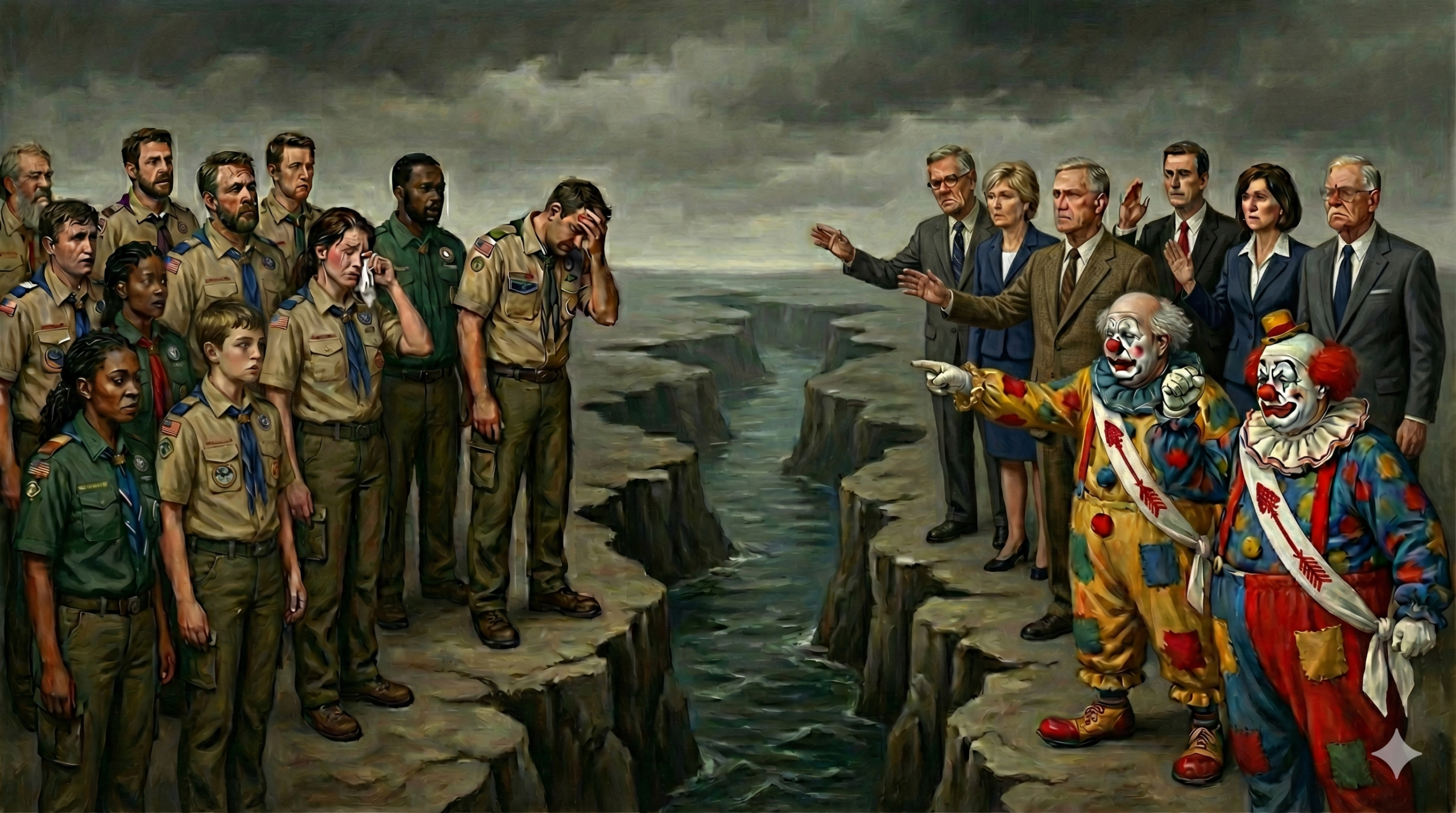

BSA’s biggest structural problem isn’t a single policy. It’s that the movement–families, youth, and unit-level volunteers–is moated off from governance. This leaves BSA with little accountability to the movement.

This has led to capture, where staff incentives dominate organizational outcomes.

BSA’s National Executive Board just cemented this capture. BSA’s rules and regulations once gave the movement a voice in governance. In an October 2025 revision, the NEB removed this.

Thanks to capture, the BSA organization‘s overriding goal is not a vibrant, relevant Scouting movement. Instead, BSA’s main goal is career protection for senior, commissioned bureaucrats.

IMPORTANT DISCLAIMER: BSA has many dedicated, productive professionals and volunteers. The problem is structural: culture eats strategy, and a small number of bad incentives can sustain bad outcomes, regardless of how many good people are trying to do the right thing.

BSA’s governance is neutered

First, a brief explanation on councils: BSA has a national organization and over 200 local councils. Local councils are like franchisees, each with a geographic monopoly to supervise program delivery. On with the story:

This is how BSA’s governance is supposed to work:

- Many positions on council boards of directors are elected by council members.

- Each council board appoints its national representatives.

- Council national representatives elect the national board of directors, the National Executive Board (NEB).

Importantly, council boards are the entry point to BSA’s governance system.

I emphasized council members above. Many members, sometimes the majority, of a council’s board are elected by council members.1 The remainder of council-board roles are mostly ex officio, meaning they are filled by virtue of one’s position within the organization. This includes council committee chairs, district committee chairs, and more.2

Let’s go back to council members, those who elect board members. Until October 2025, they were in two groups:

- Chartered Organization Representatives (CORs)

- Council Members at Large

Let’s talk about them.

Enter the chartered-organization model

In BSA’s chartered-organization (CO) model, Scout units are (on paper) an operation of community-minded organizations, such as churches and civic clubs. To become a CO, an organization signs a charter agreement (license) with BSA, which allows it to run a Scout unit.

Suppose First Presbylutheran Church becomes a CO, chartering Pack 123. Pack 123 is then a literal operation of that church, operating inside the church’s corporate veil. Everything Pack 123 does is the same as if a First Presbylutheran Church employee did it. The pack uses the church’s EIN.3

Running an operation that serves mostly external youth is a big responsibility. Enter the Chartered Organization Representative (COR). A COR is a member of the CO appointed to supervise the CO’s Scout units.

In practice, much of the above is a fiction. Few COs truly understand the contract they sign, and fully involved CORs are unusual. “Key relationships” are not uncommon. This is where the CO does little beyond handing over a building key and signing a paper once a year.

Unsurprisingly, CORs rarely showed up to council annual business meetings, where council board members are elected. Go ask any well-connected, council-level person about how many CORs show up at that meeting. All you will get is laughter. CORs didn’t show up!

Squelching the movement = institutionalism

Absent CORs mean the voice of the movement is absent from council governance. Without the movement’s voice, institutionalism prevails.

Recall that two groups used to elect board members: CORs and council members-at-large (CMALs). It appears that CORs outnumber CMALs by almost a 10:1 ratio.4 As CORs directly represent the movement, COR influence on board composition could have powerfully injected the voice of the movement into council governance.

With CORs absent from governance, electing board members is left to CMALs. Who appoints CMALs? Themselves. That’s right: CMALs themselves elect the next round of CMALs. You get a self-reinforcing dynamic where CMALs are effectively products of the institution. When products of the institution are the only ones who elect board members, this dynamic frees council boards from accountability to the movement!5

What flavor of “institutionalism” do we get? The one desired by those who dominate the institution: commissioned bureaucrats! As nearly all influential council-employee roles are gated to commissioned bureaucrats, the gravitational pull on council governance is toward the whims of the commissioned-bureaucrat system.

It doesn’t stop at councils. Institutionalist council boards appoint their own types as national representatives. These institutionalist national representatives elect their own type to the national board of directors.

At all levels, institutionalists conditioned to be responsive to the interests of the commissioned-bureaucrat system control BSA’s governance. This yields passive governance, often deferring to the whims of the commissioned-bureaucrat system. This is capture.

In a shocking turn, in October 2025, BSA cemented this capture.

What changed in October 2025

In the October 28, 2025 revision to the latest Rules and Regulations, the NEB stated that “chartered organizations will no longer be automatic voting members of the local councils”6.

If you’re a unit-level volunteer, here’s what that means in plain English:

- The movement already had weak influence in governance, courtesy of an obsolete ownership model for Scout units.

- Now the movement has little influence by design, because the only channel was removed.

This is not a minor procedural tweak. It’s a governance signal: BSA is formalizing distance between the movement (families, youth, and unit-level volunteers) and the institution (governance, bureaucrats, and support systems).

With this move, the NEB overturned at least 108 years of precedent. The earliest reference I can find is in BSA’s 1917 Constitution, which on page 33 states that “each chartered institution shall be entitled to elect one of its members … as a member of the local council”7.

Consequences of squelching the movement

BSA’s movement has been effectively squelched, subjugated to the interests of the bureaucracy, likely for at least 75 years8. Disregarding the movement used to simply be a practice. Now formalized by policy, the movement is officially no longer a priority.

This begets even more problems: mission drift, accountability void, alienation, neglect of programs and culture, and institutional mismanagement.

BSA has many, many professionals and volunteers who are productive, dedicated to the Scouting mission, and responsive to the movement. I celebrate you! But one bad apple can spoil the barrel. Scouting’s bad apples–fruits of decades of neglect of culture and programs–are driving the movement to oblivion. If we want another 100 years of Scouting, we must overcome this neglect. To get there, it is essential for us to improve governance.

Mission drift

The BSA organization has strayed from its mission. Courtesy of capture, in many ways, BSA is mainly an employment scheme for commissioned bureaucrats.

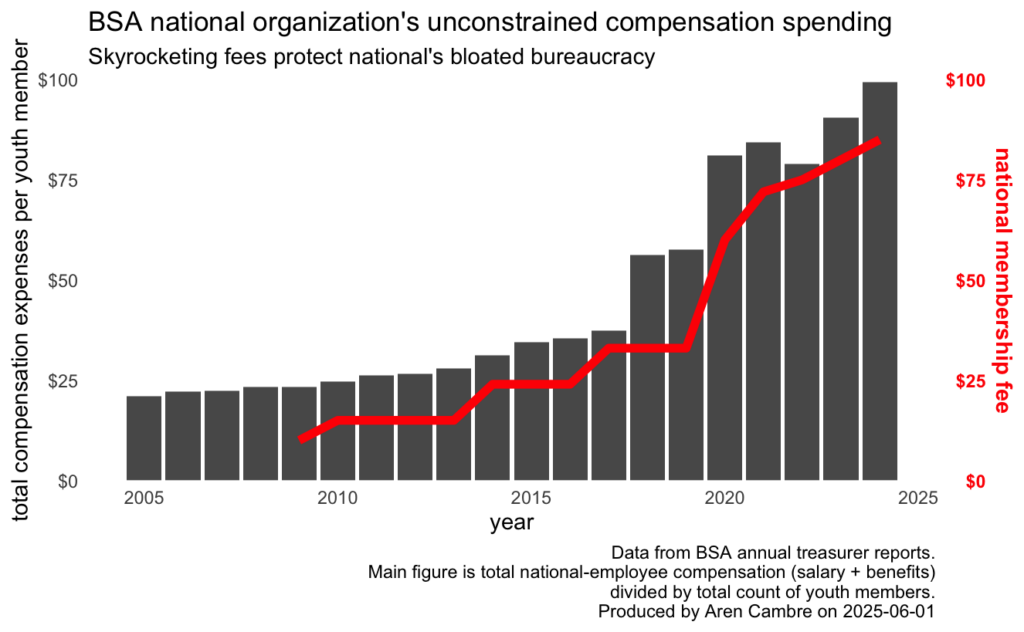

The movement often comes across as an inconvenience that commissioned bureaucrats have to deal with. We see this today with open hostility toward the movement over matters that have no merit except to maintain salary lines for bureaucrats, such as allowing councils to impose bureaucracy-preservation fees, maintaining far too many councils on the roster (inflates job roles for senior bureaucrats), or skyrocketing member fees that track skyrocketing, per-youth-member salary spend:

Disinterest in serving the movement isn’t new. Dr. Jay Mechling, author of On My Honor, reflecting on his experience in BSA in the 1970s-1990s, wrote:

The “professional Scouters,” the bureaucrats who work for the national office of the Boy Scouts of America, feel compelled to speak authoritatively about what is good or bad for children and adolescents without actually asking any young people what they think about it.9

Even today, the National Executive Board keeps allowing the national organization to flout the movement, such as:

- perpetuating religious bigotry

- permitting bureaucrats and volunteers to advance an absurd corpus of misinformation and folklore to beat down girls

- allowing bureaucrats to attack Cub Scout camping (the NEB met in the middle of this and took no public action)

- attacking feedback

- …and more.

It’s not just about malice. National’s lack of leadership talent–a product of a defective career-advancement system that prioritizes loyalty and protecting jobs–and ineffective governance opens a leadership vacuum. For decades, this vacuum has been filled by culture warriors, who squandered BSA’s treasure and goodwill. They used BSA as a tool in their societal wars on girls, gays, and God. This resulted in Pyrrhic victories, such as the landmark 2000 Supreme Court decision, Boy Scouts of America vs. Dale.

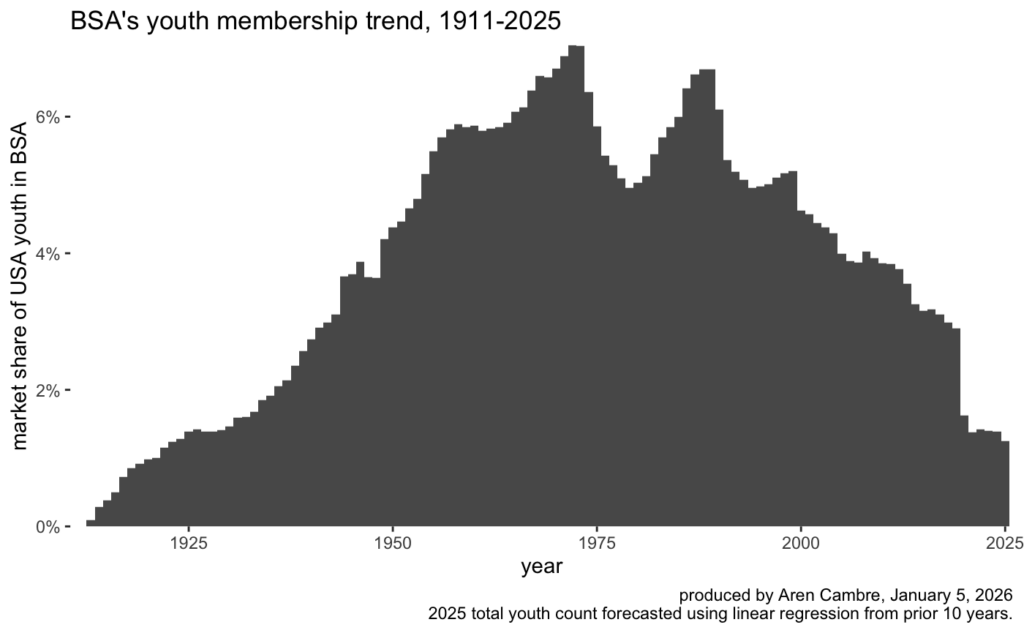

By casting a nationwide spotlight on BSA’s bigotry, this case kicked off a decades-long membership slump. Today, we are 82% below our peak market share of youth:

That slump compares poorly with The Scout Association (BSA’s peer in the UK), which is overwhelmed with demand.

This lack of leadership is also why national is just a collection of program-silos. With nobody to advocate for the movement as a whole, these program-silos optimize for their own interests and prestige.

Because BSA lacks effective leadership, inertia and neglect are the norms. This is why BSA was decades late to including girls. Even then, it took 8.5 years to cast off a misogynist-appeasement regime!10

BSA’s neglect is behind poor program designs. For example, our Scouts BSA program is stuck in an obsolete design that even Scouting’s founder, Robert Baden-Powell, rejected in 1918. This poor design infantilizes older Scouts, endangers younger Scouts, and undermines leadership training. Even worse, it undermines BSA’s most prestigious rank, Eagle Scout. Instead of meaningfully distinguishing high schoolers, 11-year-olds can earn it.11 (Solutions for all this are defined in Move Forward: Save Scouting.)

Accountability void

BSA is notorious for a lack of accountability. It stems from the You’ve Made It™️ promise to its bureaucrats. Essentially, once one becomes a senior-enough commissioned bureaucrat and has a track record of loyalty to higher-up bureaucrats, that person enters a “good ol’ boys” network, and the system pulls out all the stops to protect careers, on both the front and back sides.

The front end of career protection is how many roles are gated to commissioned bureaucrats, causing roles to be filled by bureaucrats unprepared to succeed. For example, for many decades, all national CEOs from the commissioned-bureaucrat system have been poorly prepared for their roles, with predictably poor results.

The back end of the accountability void is a culture of protecting low-performing You’ve Made It™️ bureaucrats. Stories abound of them being shuffled into low-value roles, especially at national, until they can be placed in a different council.

To facilitate accountability void, the national organization adopted a culture of indifference about competence. Otherwise, protecting low-performing bureaucrats would not be possible.

Low expectations breeds repetitive failures, such as:

- A poor implementation of a rolling-membership scheme, which is likely behind recent membership losses.

- Even though it just emerged from a colossal, record-setting, SA-related bankruptcy, national chose a new corporate name that initializes to SA (sexual assault).

- National botched the rollout of coed troops. Instead of communicating to unit leaders, national routed messaging through favored elites, then through its bureaucratic hierarchy. For weeks after the decision, troop leaders nationwide reported incomplete and absent communications on how to move forward.

Passive governance sustains the capture that allows low performers to keep getting away with it.

This accountability void doesn’t end with commissioned bureaucrats. As national-level volunteer appointments are essentially appointed by the bureaucrats or by captured governance, selection is mainly informed by the same factor that landed bureaucrats their spots: demonstrating unwavering loyalty to bureaucrats.

This is why national committees are notorious for low output, poor performance, and passivity. They hide it with a lack of transparency.

For example, the National Order of the Arrow Committee has taken five years12 just to revise children’s fantasy fiction (i.e., OA’s fake legend and the redface minstrel shows based on that legend).

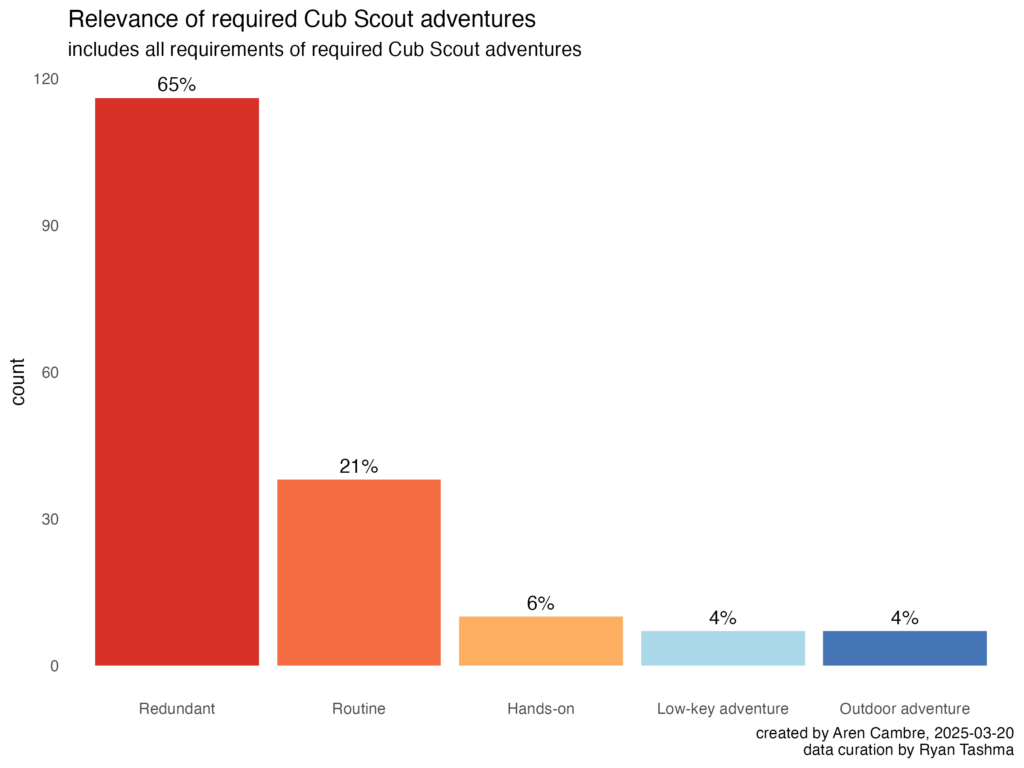

Also, in watering down Cub Scout advancement, the National Cub Scout Committee largely divorced its program’s essentials from adventure:

Alienation

Unit-level volunteers are sidelined in BSA. Receiving little meaningful support from bureaucrats, they must navigate programs created or fomented by the bureaucrats and their volunteer allies: red tape, bloated documentation, lack of program focus, and obsolete program designs.

Regarding red tape and bloated documentation, the national organization permits runaway bureaucracies to manage crucial concerns. As an example, volunteers have to wrangle a 60,000-word, 101-page document, with five levels of subsections, just to do advancement. By diverting scarce volunteer resources to serve bureaucratic nonsense, BSA’s advancement system impinges access to Scouting’s key distinction: outdoor adventure.

Essentially, volunteers are the unpaid labor force for a bureaucratic class that views them with disdain. When unit volunteers burn out from the administrative burden, the bureaucrat system engenders a culture that blames volunteers for a lack of dedication. E.g., when observing that trapping high schoolers in a middle-school program is a recipe for boredom, volunteers are blamed for problems induced by national’s faulty program design. This incentivizes continued neglect of programs and culture, not fixing the broken processes or improving obsolete designs that drove them away.

Financial and corporate mismanagement

When the movement is excluded from governance, financial priorities shift from missional excellence to sustaining the bureaucracy. This manifests in deep secrecy surrounding council and national finances; the average volunteer has little visibility into how their dues and fundraising dollars are spent.

For example, if it wasn’t buried in the bare-minimum disclosures BSA makes, few would be aware that BSA has $186 million of outstanding bond debt for SBR13, a money-losing, white-elephant vanity project. That is on top of $213 million of other debts, mainly to pay bankruptcy attorneys.

It also leads to inflated salaries for You’ve Made It™️ bureaucrats. Scout Executives (council CEOs) often command high salaries. The average Scout Executive (SE) is paid $65 per registered Scout. You read that correctly–in the average council, the first $65 collected per Scout just goes to the SE’s salary! The top 20% of SEs rake in between $91 and $352 per Scout!14 This drains resources that should be improving camps or lowering costs for families.

Where does high SE pay come from? In a dwindling number of healthy councils, fundraising. However, it appears that most councils now assess bureaucracy-preservation fees on top of the $85 national membership.

Finally, the ultimate indicator of mismanagement was the organization’s bankruptcy. Triggered by sexual abuse lawsuits, the bankruptcy was decades in the making—a direct result of passive governance that excused rampant abuse, declined to address the flawed CO model, and insulated bureaucrats from the consequences of their (in)actions.

Today, BSA’s national organization is so fiscally fragile that, at the current member-loss rate, it may have less than a ten-year runway to liquidation.

The mission is not a priority

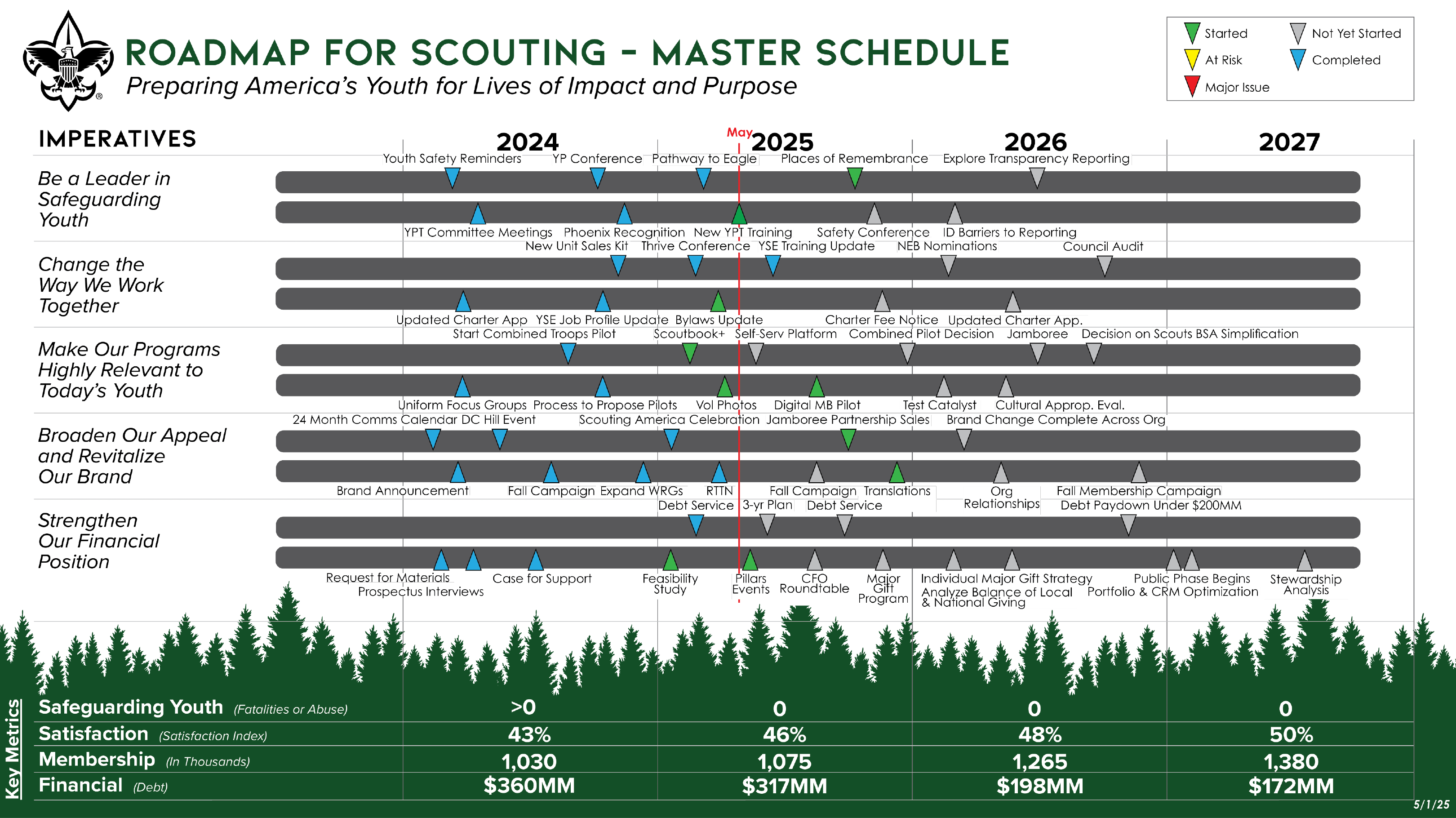

If the above isn’t enough, let’s review the current, NEB-approved institutional priorities of BSA:

Little of this is connected to serving the movement or overcoming over seven decades of neglect of programs and culture. Instead, it’s mostly bureaucrat games. Beholden to capture, governance’s priority is obedience to bureaucrats. This reveals a NEB that is mainly concerned with the institution, not with the Scouting movement.

This contrasts mightily with Baden-Powell’s vision. In response to a flunky’s proposal for a bureaucratic change, Baden-Powell rebuked him with, “WE ARE A MOVEMENT, NOT AN ORGANISATION.”15

The flunky’s proposal wasn’t bad. It was about standardization. But BP rebuked him because it was not tied to value for the movement. BP emphasized that all in Scouting are “working for the boy and not for me”.

Paths to reform

Fixing the BSA requires more than minor policy tweaks. It demands a dismantling of the structures that allowed the bureaucrat class to capture the organization.

First, we must abolish the commissioned-bureaucrat system. We must treat Scouting employment like any other job. Hiring must be based on skills and merit, not gated by ordination into a brotherhood. We need competent administrators, not career bureaucrats protected by a “good ol’ boy” network.

Second, we must abolish the chartered-organization system. This model is a grand fiction. It obscures liability and obstructs genuine ownership and accountability. We should move to a model where all units are operations of councils, with each unit governed by its own unit committee. Instead of charter agreements, councils would enter into affiliation agreements with community organizations. This maintains community affiliations while ending the shifting of responsibility and liability to third parties.

Third, the movement must have a direct stake in the organization, becoming a powerful force in governance. This starts with opening governance to the movement, giving it a major stake in selecting council boards and in determining strategic priorities.

Without these structural changes, the BSA will remain a zombie: wandering forward, eating resources, but lacking the soul and vision necessary to survive.

While changes are important, many more are needed. BSA shrinks annually because its core products are unappealing. Move Forward: Save Scouting describes many more pivots BSA needs to make to ensure another century of Scouting.

- This is a loose estimate and can vary depending on characteristics of each council. However, with the 2025 changes to BSA’s Rules and Regulations, councils now have even more power to oppose the movement. ↩︎

- More details were in the April 8, 2025 version of the Charter and Bylaws of the Boy Scouts of America, Article VI, Section 6, Clause 2. Importantly, 25-50 council executive board members were elected by the council members. I estimate that non-elected members, such as district committee chairs, council committee chairs, and a small number of other roles, would have totaled around 25 at most. ↩︎

- It is unlawful for Scout units to use any EIN other than that of their chartered organizations. Partly due to bad guidance promulgated by BSA’s national organization, it is not uncommon for Scout units to use a separate EIN from their CO. ↩︎

- Per a source at the national organization (thank you), as of fall 2025, and accounting for multiple registrations, across BSA councils there are almost 29,000 CORs and almost 3000 CMALs. ↩︎

- While this paragraph is in present tense, it reflects the April 8, 2025 revision of BSA’s Charter and Bylaws (Article VI, Section 6, Clause 1 (p. 13)). This is the revision that immediately preceded the Oct. 28, 2025 revision. Not only does the Oct. 28, 2025 revision relieve councils of any need to give CORs any say in council governance, it requires no other path for the voice of the movement to be included in council governance. Capture is powerful, so without clear incentives, it is unlikely councils will voluntarily stray from institutionalist boards. ↩︎

- Rules and Regulations of the Boy Scouts of America, October 28, 2025, p. i. ↩︎

- Constitution and By-Laws of the Boy Scouts of America, February 26, 1917 (as amended to December 31, 1925), p. 33. See the Clause 6–Representation section. Because this is prominently conveyed as a 1917 edition, I assume that the ensuing eight years of amendments, major provisions are generally intact. ↩︎

- An outcome of squelching the movement is bureaucrat culture becomes dominant, leading to bureaucracy being seen as a preferred model. A clear sign of this is how, between roughly 1940 and 1960, BSA abandoned leadership training and the patrol method in its Scouts BSA (nee Boy Scouts) program, replacing it with a youth-operated bureaucracy. This suggests that institutional capture at least goes back to around 1950 (midpoint between 1940 and 1960). ↩︎

- Dr. Jay Mechling, On My Honor: Boy Scouts and the Making of American Youth, University of Chicago Press, 2001. This book represents Dr. Mechling’s observations of Boy Scouts while he served as an adult leader for a California troop in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. ↩︎

- The misogynist-appeasement regime was kicked off by Michael Surbaugh’s platforming of misogynistic tropes in his keynote at the 2017 National Annual Meeting, then responding to them by announcing the linked-troop model and bans on coed troops and dens. Rather than promoting inclusion, as originally announced, Surbaugh’s model sought to maximize gendered separation. The national organization justified with this a shoddy corpus of misinformation and folklore. A thorough rundown is in The case for equity and inclusion: Ending BSA’s specious coed ban. ↩︎

- The shortest path to earning Eagle is 19 months. Therefore, if a Cub Scout earns Arrow of Light within five months of turning 10, that Scout could complete Eagle before turning 12. ↩︎

- In the The National Order of the Arrow Committee could care less section of OA’s pretendian core ceremonies celebrate racist oppression, mock tribes, must be blown up is a letter that substantiates that OA has been revising its children’s fantasy fiction since at least 2021. ↩︎

- See BSA’s 2024 IRS Form 990. On Schedule K, Part 1, it shows that BSA issued $225 million of bonds for SBR “[c]onstruction & equipping”. Schedule K, Part 2 shows that only $39,200,615 has been paid off. Ergo, almost $186 million remains. ↩︎

- All Scout Executive salary information comes from SE Compensation, compiled by Ryan Tashma. ↩︎

- Robert Baden-Powell, “The Hang of the Thing”, B-P’s Outlook, July 1921, p. 59. ↩︎

Leave a Reply