High schoolers do not belong in a program built for middle schoolers.

If I suggested that a high-school senior join a sixth-grade debate team, swim team, or band, I’d be laughed out of the room. That’s absurd! Yet Boy Scouts of America (BSA) does essentially this by insisting that high schoolers linger in Scouts BSA (formerly Boy Scouts), a program optimized for middle schoolers.

This weird expectation has underpinned BSA’s infamous “older boy youth problem”. This is the observation, for over a century, of how high-school-aged youth flee the program or minimize involvement.

This weird expectation is why BSA (why I don’t like the new SA name) struggles to keep teens engaged. This weird expectation causes BSA to undermine leadership training.

It’s time to take high-school youth seriously. Instead of saddling them with babysitting chores, we must provide them their own opportunities in Venturing, BSA’s excellent high-school program that already exists!

Scouts BSA is built for middle schoolers

Scouts BSA is a middle-school program. A well-run troop delivers a great program for middle-schoolers with activities aligned to their interests and abilities. The traditional troop experience–the patrol system, a focus on Scoutcraft skills, the structure of summer camps, a large part of the merit badge curriculum1, and more–is optimized for this early-adolescence cohort.

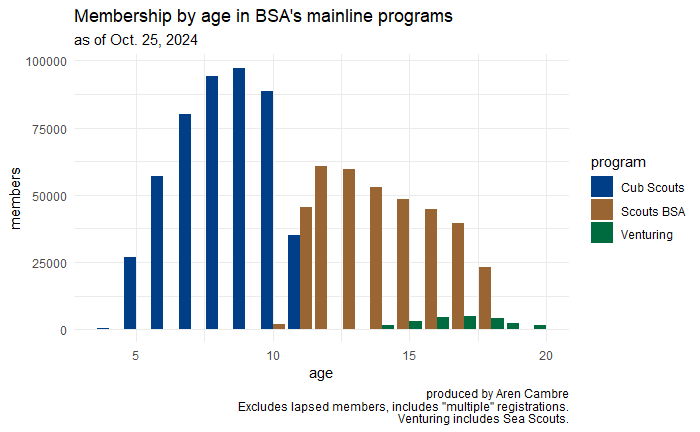

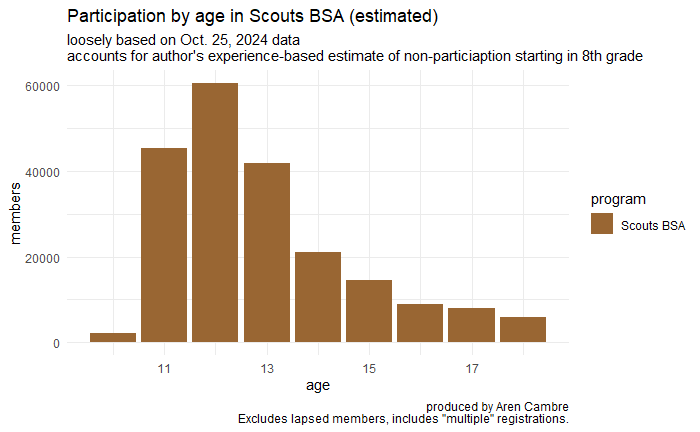

The bulk of active Scouts BSA members are middle schoolers. Each year, troops replenish with a new class of fifth-graders.

In contrast, what is the main role of a high schooler in a middle-school program? Babysitting.

Denied a peer-level program that meets their developmental needs, high-school youth in Scouts BSA are mostly just keeping the 11-year-olds in line. That’s not genuine youth leadership development. It’s just babysitting chores. This is an infantilizing experience for the high-school youth, a recipe for boredom.

Beware of those who describe this babysitting with a veneer of a Norman Rockwell painting. These stories are inauthentic nostalgia, ignoring norms of high-school and middle-school experiences.

Baden-Powell got it

It wasn’t supposed to be this way. Robert Baden-Powell is the founder of Scouting. His 1907 Brownsea Island experiment is the origin of today’s Scouts BSA program.

Baden-Powell’s experiment included youth aged 10–172 . However, he quickly realized that this included distinct age cohorts who are best served with different approaches.

BP’s musings on differentiation

Not long after his Brownsea Island experiment, and before the UK Boy Scouts Association3 (UK BSA4) was even formed, Baden-Powell started developing thoughts on distinctions between the middle-school and high-school age cohorts.5 While the details varied, his musings aligned with program separation:

- He identified a special relevance of his original Scouting program for boys ages 11 to 14.6

- He calls out ages 11-15 as when Scouts helps boys be “imbued with … patriotism and unselfishness”.7

- He proposed redesigning the program into three sections. In one case, he suggested Wolf Cubs (ages 9-11), Boy Scouts (ages 12-14), and Service Scouts (ages 14-18), with Service Scouts being a alternative to “compulsory Cadet Training”.8 In another case, he proposed preparatory (8-11), character (11-16), and civic (16-18) sections.9

- He differentiated between the suitability of the British Army’s cadet program for “older boys” (roughly ages 15+) versus the “young ones” (roughly 11-14).10

- He proposed a program at “continuation schools” for “all boys of fourteen to sixteen”.11

- He characterized troops where different age cohorts are combined as “ridiculous”.12

- In 1916, he laid out a preliminary plan for providing a differentiated program for “Elder Scouts” that is more relevant to their life stage, which he found to be distinct from the 11-14 cohort.13

Scouts Defence Corps

A brief experiment with the Scouts Defence Corps, starting in 1915, aided retention of boys aged 15-years-old and up. This program’s termination placed this cohort’s retention problems back on Baden-Powell’s mind:

Many Scouts Defence Corps Officers noted that their membership had been made up of older lads who were leaving their Scout Groups at 15-plus, as there were no specific activities or badges for lads of this age group at that time. With the demise of the Defence Corps, ‘retention’ became a major problem and in answer to it the Senior Scouts Section was started 1917.

Colin Walker, “The Scouts Defence Corps and ‘The Red Feather’“, “Johnny” Walker’s Scouting Milestones

Rovers, for ages 15 and up

As mentioned in the above quote, a Senior Scouts section was started in 1917.

Baden-Powell proposed formalizing this as Rovers, which was to be for ages 15 and up. In his September 1918 book, Provisional Rules for Rover-Scouts, 6th Edition, Baden-Powell started with an impactful preamble14 (“older lad” refers to the boys 15 and older, roughly correlating to modern USA high-school ages):

It is obvious that just as the boy of 8-11 is constitutionally different and requires different training from the boy of 11-15, so the older lad, developing into manhood, requires a separate education and treatment of his own. The loss from the Scout Movement of many of these lads … is due … to the constant repetition, without novelty, of the old Tests and games. The older lads want to do bigger things, to do things as men do them, and to have more vigorous Scouting work than that which is applicable to the lower mental and physical capacity of the younger boys.

Provisional Rules for Rover-Scouts, 6th Edition, The Boy Scouts Association (UK), Sept. 1918 (emphasis added)

Provisional Rules for Rover Scouts laid out how Rover Scouts were to operate. Meant to employ Scouting fundamentals similar to those in Scouting for Boys15, this publication defined a program for “for Scouts over fifteen”16. In other words, Baden-Powell found that Scouting’s universal tenets need different approaches for age cohorts that map to today’s middle-school and high-school life stages.

Just as Wolf Cubs got a program distinct from Scouts (“Scouts” refers to Baden-Powell’s original program, still named Scouts today in the UK, and that maps to the Scouts BSA program in BSA), Baden-Powell recommended Rovers also get a program distinct from Scouts17:

The Rover Patrol must have its own separate hour or night for meeting. This may present a difficulty. One solution is the holding of the Rover meeting after the Scout troop has finished its evening’s work in the same room. The boys will prefer, however, to have their own meeting place, which is always open to them, or to which all have keys.

Provisional Rules for Rover-Scouts , 6th Edition, The Boy Scouts Association (UK), Sept. 1918, p. 5 (emphasis added)

While Baden-Powell’s Provisional Rules for Rover Scouts made a great case for differentiation, his organizational improvements were shot down. In June 191818, at a meeting Baden-Powell could not attend, the 15+ cohort was excluded from Rovers.19 Rovers was changed to an early-adult program, with a minimum age of 17.20 This course change was because accommodating young soldiers, starting to stream back from World War 1 tours of duty, was viewed as urgent.21

Aids to Scoutmastership

In Aids to Scoutmastership, Baden-Powell writes:

[Scouting] is a game in which elder brothers (or sisters) can give their younger brothers healthy environment and encourage them to healthy activities such as will help them to develop CITIZENSHIP.

Robert Baden-Powell, Aids to Scoutmastership, 1919, p. 13

A facial read may lead one to believe Baden-Powell believes that older Scouts are who give younger Scouts this game. In fact, Baden-Powell uses “older brother” to describe adults!

Later in Aids to Scoutmastership, Baden-Powell describes the right adult leader as a “Boy-Man” who not only must “realise the psychology of the differen’t ages of boy life” but also “has got to put himself on the level of the older brother, that is to see things from the boy’s point of view, and to lead and guide and give enthusiasm in the right direction.”22 He reinforces with that moral education needs a “a close confidence between teacher and pupil, on the relationship of elder and younger brother”.23 He tempers with that the Scoutmaster “brings a great responsibility on himself” because “[i]t is easy to become the hero as well as the elder brother of the boy”.24

In all this, Baden-Powell is reinforcing the adult association method of Scouting. That is a remarkably different vision than BSA, where adults commonly abdicate adult association, barking “Ask your SPL!”25 Abetting this abdication is a long-failed experiment. In this experiment, BSA undermines the high-school experience, mostly reducing it to babysitting chores. Also, the most important youth role, the Patrol Leader, is undermined by being lost in a fog of youth-operated bureaucracy. More on this later.

Finally, in the book’s introduction, Baden-Powell criticizes Cadet training because it treats boys in different life stages “all on the same footing.”26 He contrasts it to “Scout training”, which provides differentiated programming for “seniors and juniors27…to meet the different stages of the boys’ progressivity.”28

UK achieves BP’s vision in 1967

Baden-Powell’s vision for differentiated programming for seniors and juniors wasn’t fully met for decades. He was frustrated by this, with a biographer saying he “deplored” the slow speed in starting programs for older Scouts, to the point where in response to this stalling, he was once observed “raging at the rotten way in which the Committee try to put on the brake and the disgracefully ungrateful manner in which they behave”.29

Back to 1918, once the age for Rovers was increased to 17, older youth were sent back to the middle-school program, and it stayed that way for the remainder of Baden-Powell’s leadership in UK BSA.

In 1946, UK BSA created a modest differentiation, called Senior Scouts, for ages 15-18.30 This still operated in troops, alongside the ages 11-14 Scouts. A UK citizen, who was a Senior Scout in the 1950s, described the experience as a mix between independence and activities this author found closely resembled BSA’s babysitting regime.

It wasn’t until a late 1967 reform31, driven by the Advance Party Report, that Baden-Powell’s vision was fully realized. Along with the UK BSA renaming itself The Scout Association (TSA), it created a separate section for ages 15.532-20 named Venture Scouts33. Today, this section is known as Explorer Scouts and is for ages 14-18.34

TSA is now joined by 100% of BSA’s international peers in providing separate Scouting opportunities for middle-school and high-school youth. Stuck way in the past, lagging behind its international peers, and fighting rational norms of the country it serves, BSA infantilizes its high schoolers, saddling them with babysitting chores while keeping them in middle-school purgatory.

Ernest Thompson Seton got it

Ernest Thompson Seton came up with several core ideas of Scouting in Woodcraft Indians, which he founded in 1901. Intrigued by Seton’s ideas, Baden-Powell adopted core aspects of Seton’s Woodcraft Indians into his fledgling Scouts program.

Seton became a founder of BSA. By the time he co-authored BSA’s first Official Handbook in 1910, Seton had almost a decade of experience with youth. The Handbook‘s introduction includes Seton’s nine “leading principles”. In principle 8, “A Heroic Ideal”, Seton wrote that “[t]he boy from ten to fifteen … is purely physical in his ideals.”35 With this, Seton was implicitly bracketing the core age where the Boy Scout program had most relevance.36

This age band wasn’t accidental. The same statement appears a few years later, in Seton’s The Book of Woodcraft37, which reignited his Woodcraft Indians program after he was pushed out of BSA38.

BSA’s international peers get it

As mentioned above, BSA stands out from its international peers by infantilizing high schoolers, forcing most to linger in a middle-school program, saddled with babysitting chores:

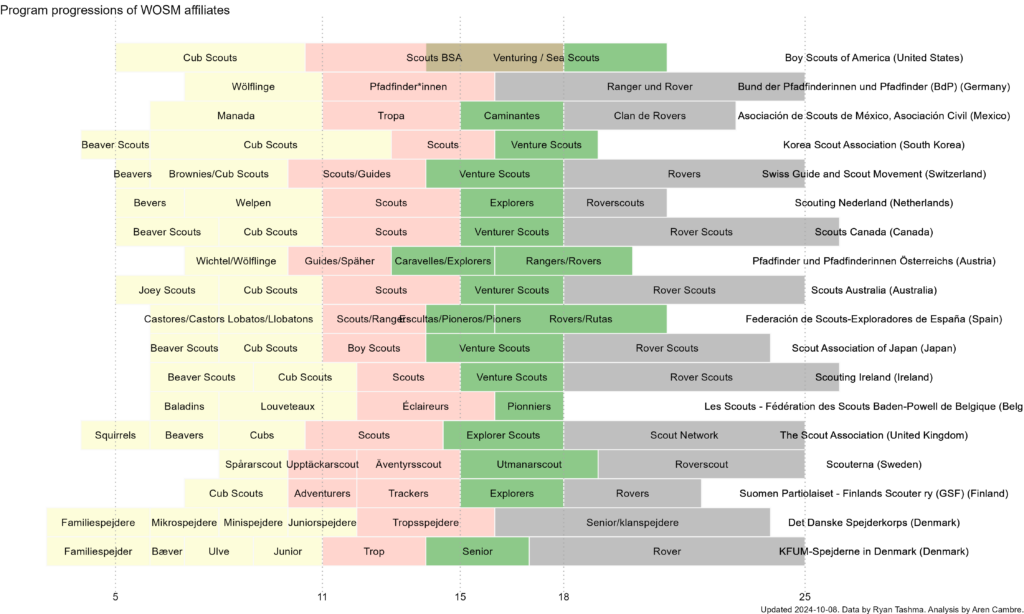

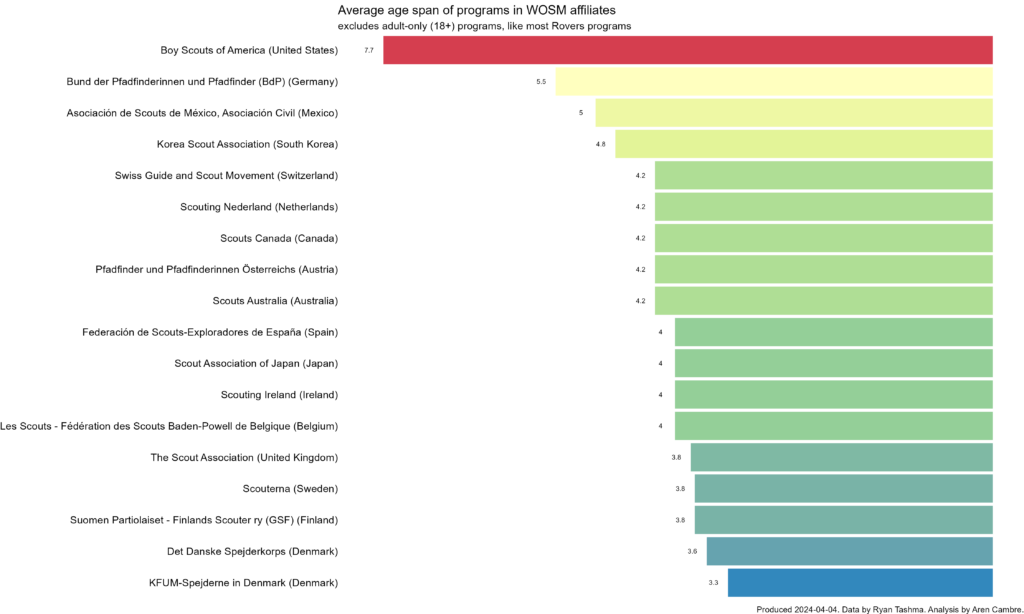

Red bands roughly map to USA middle-school ages, and green bands roughly map to USA high-school ages.39

BSA’s brown band is where its middle- and high-school programs overlap, competing for members. Per data shared later, the vast majority of BSA’s high schoolers are stuck in its middle-school program!

Further harming BSA’s programs (Cub Scouts, Scouts BSA, and Venturing40) are how many ages BSA crams into each. BSA sticks out from its WOSM peers in its huge per-program age range, which leads to unfocused, diluted programs:

Contemporary adolescent psychology is aligned with program separation

USA educational system organized around adolescent developmental stages

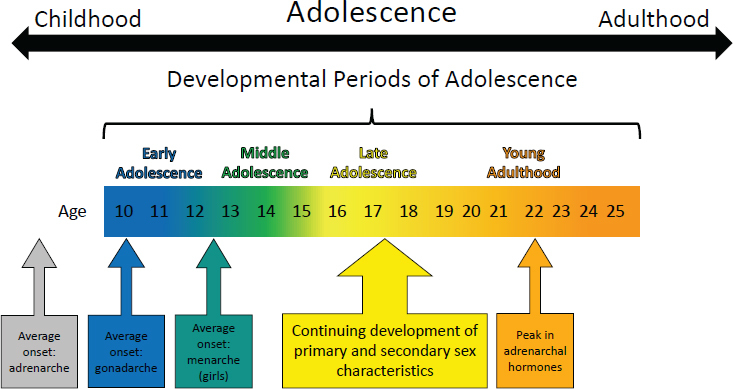

Numerous peer-reviewed research articles or quality publications cluster adolescents into age bands. The National Academies of Science gives an example41:

This is just one example. The age bands’ names and brackets vary between publications.

For this article, I will use the age bands as defined by Professor John P. Cunha, DO42 and others, which are aligned to societal norms of middle-school, high-school, and post-high-school life stages:

| Life stage | Grades | Ages |

| Early adolescence | 6-8 (middle school) | 11-14 |

| Middle adolescence | 9-12 (high school) | 14-18 |

| Late adolescence | early adulthood (after high school) | 18-25 |

An aside on the middle-school concept

While it is beyond the scope of this article, you are invited to review the history of the USA middle-school concept. Before this concept emerged, children up to 8th grade were generally in elementary schools (primary education), and grades 9-12 were generally in high schools (secondary education).

The kickoff to today’s customary middle schools was Indianola Junior High School, which in 1909 took on grades 7 and 8.43

Importantly, education was improved by differentiating service to different life stages with different programs.

Importantly, there has never been a serious movement to adopt a model like BSA, merging middle schools with high schools. That would be absurd.

Adolescent developmental stages

Adolescence is a complex set of concurrent changes. Kicked off by puberty, adolescence “involv[es] a number of physiological and structural changes that tend to occur over a variable time period.”44 The timing and pace of each change has variable individual expression.45 Still, reasonable norms can be established for adolescent life stages:

| Factor | Early Adolescence (middle school) | Mid-Adolescence (high school) | Late Adolescence (after high school) |

| Growth | Rapid growth spurt, height and weight increase | Rapid growth, approaching adult height | Adult height |

| Pubertal changes | Onset of puberty, sexual characteristics develop | Sexual maturation continues, mostly completes | Hormone levels stabilize |

| Cognitive ability | Mostly concrete and black-and-white, limited abstract reasoning | Abstract reasoning and problem-solving improves, but still impulsive | Advanced abstract thinking, hypothetical reasoning |

| Romantic interests | Emerging interest in crushes, infatuations | More intense relationships, intimacy more important | Developing long-term, enduring relationships |

| Gender-identity expression | Exploration of gender roles & societal norms, may question gender identity | Exploration intensifies, peers influence expression | More stability, with self-acceptance |

| Peer Influence | Peer approval and conformity important | Peer influence narrows, risk taking in line with peer norms | Moderated by independence, identity, and life goals |

| Interest in body changes | Curiosity and anxiety about rapid change, concerns about normalcy | Body image concerns persist, focus on body acceptance | Less preoccupation with appearance, shifts to style and fitness |

| Gender relations | Cross-gender friendships start to appear | More mixed-gender friendships, romantic interest can drive this further | Mature cross-gender friendships, romantic partnerships |

| Leadership capability | Participation in group activities | Leadership abilities emerging | Leadership roles in academic, social, or work settings |

| Independence | Seeking autonomy, desire for independence from parents | Increased arguments with parents, independent decision-making | Increasing independence, self-reliance, and responsibility |

| Desire for sexual exploration | Curiosity, exploration of sexual feelings and attractions | Heightened interest, experimentation, masturbation | Developing sexual identity, forming intimate relationships |

There’s room to disagree on the details of this table. The main point is of significant differences between these life stages. You are invited to dig deeper into research articles and other resources in Appendix A.

Societal norms set helpful expectations

These life stages are also USA’s societal norms, deeply ingrained. Our educational system is set up around them, and it’s common for youth-serving programs to use them.46 These norms help set expectations for risk management and acceptable intra-cohort differences.

Society has not conferred wide acceptance of combining different age cohorts as peers in the same program. For example, it is unusual to slice off only ninth grade and place it in middle schools.47 This, plus the rationale for how each cohort maps to a distinct developmental phase, exposes us to risk and program-quality problems when we combine different stages as program peers.

Returning to societal norms, consider a problematic interaction between an 8th grader and a 6th grader. Middle schools deal with this all the time, so abundant experience and guidance is available. That’s far different than, say, a problematic interaction between a new, 10-year-old, 5th-grade Scout48, who is attending her first campout in a Scouts BSA troop, and an experienced 12th grader49, who are peers in Scouts BSA due to BSA’s poor program design50.

Deviating from these cohorts, especially with no rational basis, is ill-advised. But that is BSA’s approach!

These cohorts benefit from distinct approaches

Due to considerable differences between middle schoolers and high schoolers, different approaches are beneficial.

One example is a dramatic difference in sexual experience. For example, 17-year-olds are 1300% more likely to have had sex than 11-year-olds.51 While I support BSA’s prohibition of sexual activity at Scout events, an adult leader’s approach for high schoolers will be different than the approach for younger cohorts.

This also includes big differences in an ability to learn and practice leadership.

First, a crucial note: I am using an authentic meaning of leadership for this article. Widespread confusion causes many to conflate leadership with administration and management. Leadership is about a vision for change and voluntary followership, not about hierarchies, formal roles, completing checklists, etc. This is covered in more depth at Unleash True Leadership: Break Free from BSA’s Outdated Program Design.

Per the above chart, emergence from black-and-white thinking into abstract reasoning and gaining an ability to manage peer influence–among several factors crucial for one to be a true leader–occur during the high-school life stage.

While middle schoolers are not devoid of capacity to learn leadership, their ability is in a much different state than high schoolers. Leadership training acceptable for middle schoolers is too dumbed down for high schoolers.

We could continue, compiling a long list of substantiative differences between middle schoolers and high schoolers where program differentiation is beneficial to each cohort. With its head in the sand, BSA clings to obsolete thinking, that 17-year-olds should be peers to 11-year-olds in the same program.

BSA bastardized it

Contrary to its international peers, BSA rejects Baden-Powell’s and Seton’s wisdom, it rejects USA societal norms, and it rejects science. Instead, BSA bastardizes the high-school Scouting experience.

With no evidence supporting its stance, BSA clings to the myth that high schoolers are best served by lingering in its middle-school program as babysitters. This fairy tale pervades BSA’s decades of failure at serving high schoolers.

BSA has always insisted on babysitting chores for high schoolers

In BSA’s first guide for high-school programming, it formalized this myth in a 1938 publication, The Guide Book of Senior Scouting.

In Guide Book, in a section titled “The Psychology of Young Manhood”, BSA lays out a great, 12-point case for why high schoolers are different than middle schoolers.

SA then goes incoherent. After making a great case for program separation, BSA recommends infantilization, insisting that high schoolers remain in middle-school purgatory:

…upon reaching the age of 15 the Scout may acquire the status of Senior Scout which accords him certain privileges and responsibilities but which encourages him to remain as a Scout in the Troop except in special situations…

The Guide Book of Senior Scouting, Boy Scouts of America, 1938, p. 9 (emphasis added)

Why does BSA want the high schooler to “remain as a Scout in the Troop”? In various places in Guide Book, BSA makes clear that age-appropriate programming is provided under the expectation that older Scouts continue their babysitting chores.

Few high-school units exist

BSA has been quite successful in failing high schoolers. First, for its 115 year history, it has never truly tried to solve the older-youth problem. To do that, BSA must leave behind obsolete ideas, especially the babysitting regime.

BSA’s insistence on high schoolers remaining in middle-school purgatory is evident in availability of each type of unit. As of October 15, 2024, BSA has about a 10:1 ratio of middle-school units to high-school units:

- 20,148 middle-school units (Scouts BSA troops) (91%)

- 2,012 high-school units (Venturing crews) (9%)

In terms of youth-member count, high-school programs barely have any youth. See the green Venturing bars:

The vast majority of BSA’s high schoolers are stuck in middle-school purgatory.

Many high-school units are sabotaged

Even worse, the integrity of many of these high-school units is questionable. Much of BSA’s alleged high-school programming may be a subterfuge.

Over 3/4 of crew members are simultaneously registered in a troop. This pits crews against the middle-school program, competing for high-schoolers’ time. Combining BSA’s longstanding expectation of high schoolers remaining in middle-school purgatory with that few high-school youth have the time to fully invest in more than one Scouting program, dual-registered youth likely feel they must allowing babysitting chores to crowd out age-appropriate programming.

Even worse, I am aware of “in name only” Venturing crews. Some are de facto patrols of the middle-school program. Some are created mainly to enable the middle-school program to get high-adventure slots. Some are routinely sabotaged to assure availability of babysitters for the middle-school program. Some are created mainly to provide a BSA membership to those to want to participate in BSA’s weird, racist, secret society.

Few high schoolers are active in troops

Per above, in the original Scouts program in the UK, it was notable how youth aged 15 and older fled troops. BSA is no different.

In 1938, BSA had 830,878 troop members52. 78% were ages 12-14, and only 21% were ages 15-17. Attrition was about 50% between ages 15 and 1653.

Today has a similar trend, although the above graph misrepresents it. In that graph, it looks like attrition through Scouts BSA is linear and modest. It’s much worse.

This graph only indicates who paid BSA’s annual membership fee. It does not show who is active. With dreams of Eagle Scout ranks helping with scholarships, college placement, careers, and more, many parents freely pay annual membership fees for their inactive youth.

High schoolers are largely rejecting their babysitting chores. Many are inactive. This is easily observable in typical troop meetings or activities: the proportion of high schoolers participating is drastically lower than indicated above. While this is my own qualitative view, I have seen many, many troops from the 1990s through now. Robust high-school-age participation is unusual.

It’s even apparent in Dr. Jay Mechling‘s excellent book and ethnographic study, On My Honor. Covering his observations of a California troop over three decades (1970s through 1990s), he describes a troop well known for having four middle-school patrols of around 8 Scouts each and one “Senior” patrol of high schoolers.54 This is a lopsided ratio of 4:1 middle schoolers to high schoolers. In other words, most Scouts fled this troop before their role transitioned to babysitting.

Disgusted with babysitting, waiting until last minute to get Eagle

More suggestive evidence comes from BSA’s own statistics on the average age when youth earn their Eagle Scout rank. It is 17.3 years old.55

This only an average. It includes all ages, even 12-year-old “paper Eagles”. For the average to be 17.3, there are likely an outsized number of youth who earn Eagle very close to their 18th birthday, the deadline to perform all work for the Eagle Scout rank.

Why so old, for a badge program normally started when 10 years old? The high schoolers who don’t flee the babysitting regime are minimizing involvement in Scouting. They do the bare minimum needed to prevent parental nagging.

The typical Eagle Scout-rank earner resurfaces disturbingly close to the 18th birthday to hold his or her nose, resuming babysitting chores while knocking out the last part of the Eagle Scout rank.

Reconstruing the above graph to show Scouts who are actually active in their troops, I estimate numbers more like this:

This illustrates the precipitous drop-off in troop participation that starts to really take hold in 8th grade. Why does the sag start in 8th grade? Look at their perspective: As they look forward to new high-school experiences, they see that BSA only provides more years in a program they are rapidly outgrowing!

High schoolers are singled out for babysitting chores

Babysitting is when a program’s main job for one cohort is to supervise or otherwise serve a younger cohort. That’s precisely BSA’s customary expectation for high schoolers who linger in its middle-school program (Scouts BSA).

Let’s look at this more broadly:

- Is the best and highest purpose of grades 3-5 to supervise grades K-2? No!

- Is the best and highest purpose of grades 6-8 to supervise grades 3-5? No!

Those would be absurd. We accept that grades 3-5 and 6-8 deserve age-appropriate programming. Babysitting chores are not that.

Why does the narrative change for grades 9-12? Why does BSA believe that, unlike other age cohorts, grades 9-12 are to be undermined, forced to supervise middle-schoolers? Why does BSA deem high schoolers unworthy of age-appropriate programming?

Babysitting is the main point of shackling high schoolers to Scouts BSA!

High schoolers don’t like it

“But my high schoolers love my troop! [snort]”

-Rando adult leaders, while clutchingpearlsWood Badge beads

I’ve heard several adult leaders glowing over how their high schoolers appreciated the opportunity to mentor middle schoolers.

Some youth thrive on serving younger cohorts. I love it when youth have these aptitudes! I propose that we support these youth in a much better way with a new servant-leadership role, called Guide.

But my consistent experience is few youth have this interest or aptitude. I did not when I was a youth. My sons didn’t. Nothing is wrong with us. We were normal.

The adult leaders’ glowing comes from selection bias. This is when one takes readings from a biased sample, then improperly generalizes findings from those readings.

Here’s an example of selection bias. Imagine you’re trying to find out if people like spicy food. If you only survey customers at a hot-sauce shop, you’ll conclude that most people enjoy spicy food. That’s because you’re only talking to people who already like spicy flavors, not everyone in the general population. This is a simple example of selection bias, where your sample isn’t representative.

The above Scoutmasters’ biased sample are because youth who remain active in a troop are largely those who tolerate babysitting chores. That, plus a cultural expectation of deference to adults, of course adults will hear positive stories about babysitting chores. However, these adults are ignoring the voice of the vast majority of high schoolers, who fled or quiet-quitted BSA’s babysitting program.56

Bells and whistles don’t change this

“But OA and high adventure and camp staffing keep them involved! [snort]”

-Rando adult leaders, while clutchingpearlsWood Badge beads

BSA’s main strategy for high-school retention isn’t a relevant program. Instead, it’s to distract from babysitting chores with shiny objects. BSA does this with mainly camp staffing, high adventure, and a weird, racist, secret society.

These shiny objects don’t change that the main program for high schoolers is the babysitting regime. In the same sense, adding shiny decorations to a Christmas tree does not change that it’s a tree.

To experience these shiny objects, youth must be registered in a Scout program. For the vast majority of high schoolers, this means registration in the middle-school program, Scouts BSA. Therefore, the core Scouting experience for most high schoolers is the babysitting program.

When the high schooler is done with the shiny-object activity, that youth returns to babysitting chores in the troop.

Even worse, with its belief that shiny objects retain high schoolers, BSA admits that the middle-school program fails to retain them! In other words, BSA has high schoolers escape the middle-school program to find age-appropriate opportunities!

So sure, your high schoolers can go to Philmont. It’s a good experience, and I recommend it! But when the Philmont experience is done, they return to babysitting chores in the middle-school program.

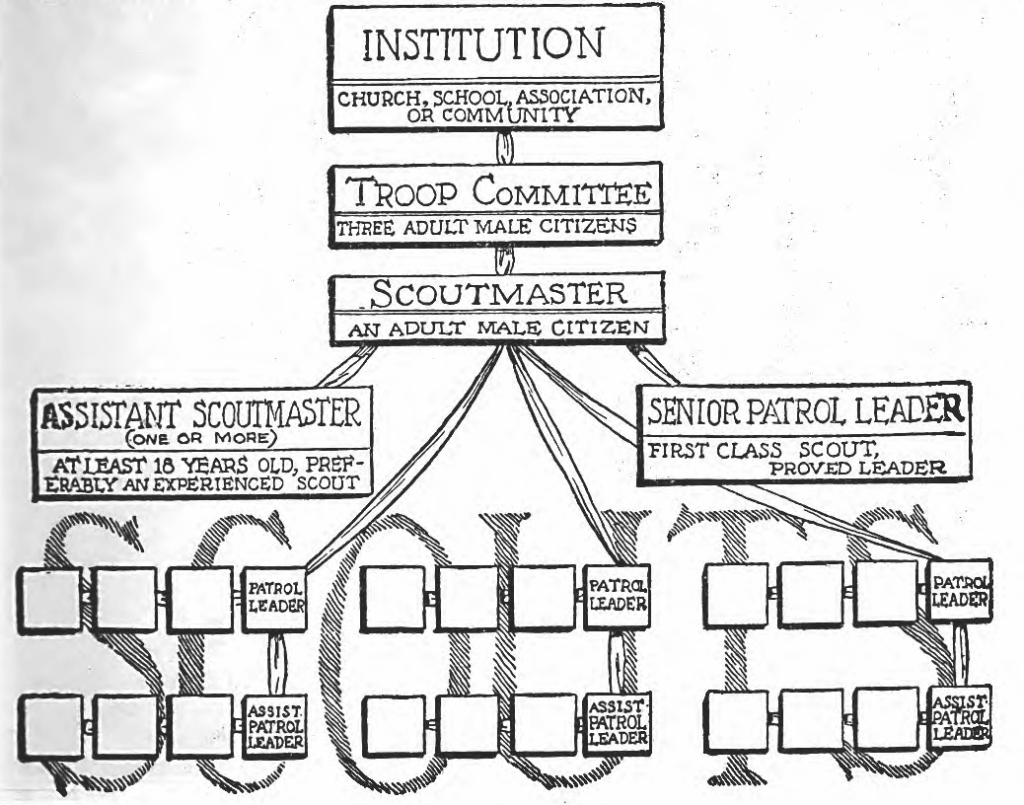

BSA’s patrol method is not a leadership training tool

The patrol method used by BSA is not Baden-Powell’s patrol method.

Baden-Powell’s vision was of independent patrol-teams that acted on visions coordinated by adult leaders. He had no Senior Patrol Leader role.

BSA started with Baden-Powell’s patrol method. This is the troop-organization system in 193257:

Note how the Patrol Leaders report to the Scoutmaster.

BSA later warped the patrol method into a mini bureaucracy. Due to this, Scouts BSA is not a genuine patrol method. Instead, it’s management and administration bureaucracy that suppresses leadership. This design undermines the Patrol Leader role. Instead of leading a team towards visions, Patrol Leaders are more of a cog in a bureaucracy, focused on wading through a bureaucratic fog while implementing concrete orders of a Senior Patrol Leader. This is especially tragic as the Patrol Leader is the most important direct-contact position of responsibility in a troop.

Speaking of “position of responsibility”, this is among the few things BSA is getting right. BSA increasingly uses this label for what used to be called “youth leadership roles”. Since the Scouts BSA bureaucracy discourages leadership, “position of responsibility” is more accurate.

High school is the life stage where abilities aligned with leadership start to “turn on”. For high schoolers to get leadership experience, it’s important to rip off the patrol method’s training wheels. This requires a different approach than Scouts BSA. I go into this more deeply in Unleash True Leadership: Break Free from BSA’s Outdated Program Design, an article about opportunities for BSA to embrace leadership, instead of undermining it.

A well-run troop is a great middle-school program

“Well, you’re losing high schoolers because you just don’t know how to run a troop right. [snort]”

-Rando adult leaders, while clutchingpearlsWood Badge beads

Scouts BSA is aligned to the life stage of middle schoolers. The vast majority of active troop members are middle schoolers. Each year, troops that thrive get a new, large class of Scouts near the end of their fifth grade year.

If you’re running a troop right, you’re running a great middle-school program! High schoolers will naturally feel unserved by this.

Some claim to have bucked BSA’s failed approach, instead offering differentiated, age-appropriate programming for high schoolers. In fact, these youth are still poorly served. They can’t rip off the patrol method’s training wheels, their babysitting chores rarely go away, and their main, age-appropriate programming comes from fleeing the middle-school program for the shiny objects. This is not a substitute for an age-appropriate program.

Start serving high schoolers, stop the infantilization

For 115 years, BSA has chosen to infantilize high schoolers, keeping them in middle-school purgatory. Due to this choice, BSA serves high schoolers poorly, and it lags decades behind its WOSM peers and defies the society it’s supposed to serve.

BSA’s disregard of high schoolers remains strong today:

- In multiple closed settings in recent years, senior national executives have voiced a desire to cancel all high-school programming.

- The national organization conspired to destroy older-youth opportunities with its 2019 Churchill Plan.

- In 2024, the national organization arbitrarily annihilated well regarded Venturing training programs, destroying Kodiak and wrecking Power Horn. Showing contempt for the base, national conspired in extreme secrecy, then it laughably promised a lackadaisical, secretive approach to a “review”.

- The national organization generally provides minimal support to Venturing.

BSA is in year 115 of its failed experiment of trying to solve the “older [youth] problem”. This failed experiment is a Sisyphean quest. Until it stops infantilizing high schoolers–expecting them to remain in middle-school program–BSA will eternally push a rock up a hill.

To move past this, BSA must make two program changes:

- Change Scouts BSA a grades 6-8 program.

- Make Venturing a grades 9-12 program.

This change creates a new norm, where high schoolers benefit from a program focused on their life stage. Freed from the babysitting chores and from the patrol method’s training wheels, high schoolers can, for the first time in BSA’s history, have an unencumbered opportunity for leadership training.

This change provides opportunities, such as:

- Guides, a superior way for older cohorts to provide voluntary service to younger cohorts

- Strengthened, more relevant First Class and Eagle Scout ranks.

- Age-appropriate programming that may retain high schoolers.

Venturing’s elephant in the room

As much as I like Venturing, it has an elephant in the room.

Like Scouts BSA, Venturing covers too many ages, ranging from 1358 to 20. This combines high school and early adulthood into one program. I won’t re-litigate my above arguments, but parents, you’re right to question why your 8th grade kiddo is a program peer to a 20 year old college sophomore! That is super weird! But super weird is normal in BSA.

Why such a large span? In 1971, BSA increased the cut-off age of Exploring, Venturing’s predecessor program59, from 18 to 2160. While I cannot find a definitive source to confirm this, some references suggest it was yet another boneheaded decision of the national organization, this time to shot up those wanting Rovering.

Rovering is generally a Scouting program for ages 18-25. It offers age-appropriate programming for young adults.

To correct the elephant in the room, BSA needs to restrict Venturing to high school, meaning grades 9-12. Yes, this means 14 year old 8th graders may no longer be a part of Venturing. It starts for everyone once 8th grade is done.

Importantly, the last year must generally allow all 12th graders to be genuine peers, regardless of age. It would not be acceptable to revisit BSA’s failed Churchill Plan conspiracy to destroy Venturing, which proposed to eject youth members on their 18th birthday, effectively gradual ejection of all youth at random and arbitrary points during the 12th grade year.

It is also crucial that 18-year-old 12th graders are in no way separated from or treated differently than their under-18-year-old high school peers. For example, a high schooler who just turned 18 may still buddy-pair or tent with her 17-year-old friend. This means that for youth members of Venturing, BSA’s differential treatments prescribed for adults are deferred until high-school graduation.

BSA also needs to start Rovering. This starts at high-school graduation and ends around age 25.

Appendix A: More reading on stages of adolescence

In no particular order, this is suggested research that can provide more insight on the stages of adolescence:

- Alan D Rogol, M.D., Ph.D., James N Roemmich, Ph.D., Pamela A Clark, M.D., “Growth at puberty“, Journal of Adolescent Health, December 2002.

- Elizabeth J. Susman, Alan Rogol, “Puberty and psychological development“, Handbook of Adolescent Psychology, Second Edition, 2004.

- J. Piaget, “Intellectual Evolution from Adolescence to Adulthood“, Human Development, 1972. Also suggested: Laurence Steinberg, Age of Opportunity: Lessons from the New Science of Adolescence, Sept. 9, 2014.

- W. Andrew Collins, “More than Myth: The Developmental Significance of Romantic Relationships During Adolescence“, Journal of Research on Adolescence, February 13, 2003

- American Psychological Association, “Guidelines for Psychological Practice With Transgender and Gender Nonconforming People“, American Psychologist, December 2015

- Whitney A Brechwald, Mitchell J Prinstein, “Beyond Homophily: A Decade of Advances in Understanding Peer Influence Processes“, Journal of Research on Adolescence, February 15, 2011

- Britany Allen, MD, FAAP, Helen Waterman, DO, “Stages of Adolescence“, Healthy Children, American Academy of Pediatrics.

- Jennifer L. Tackett, Kathleen W. Reardon, Nathanael J. Fast, Lars Johnson, Sonia K. Kang, Jonas W. B. Lang, and Frederick L. Oswald, “Understanding the Leaders of Tomorrow: The Need to Study Leadership in Adolescence“, Perspectives on Psychological Science, November 9, 2022.

- Brittany Allen, MD, and Helen Waterman, DO, “Stages of Adolescence”, Healthy Children: The AAP Parenting Website, American Academy of Pediatrics, April 29, 2024

- “Core Concepts – Adolescent Medicine”, The University of Texas Medical Branch

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; Board on Children, Youth, and Families; Committee on the Neurobiological and Socio-behavioral Science of Adolescent Development and Its Applications; Backes EP, Bonnie RJ, editors. The Promise of Adolescence: Realizing Opportunity for All Youth. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2019 May 16. (see figure 2-1)

- Margaret E. Gutgesell, MD, PhD, and Nancy Payne, MD, “Issues of Adolescent Psychological Development in the 21st Century“, Pediatrics in Review, American Academy of Pediatrics, 2004

Footnotes

- Many merit badges speak more towards the middle-school life stage or are Scoutcraft-oriented. ↩︎

- Brownsea and its significance – The world’s first Scout Camp, “Johnny” Walker’s Scouting Milestone Pages, accessed on 2024-10-25. The boys were 10-17 years old. ↩︎

- The formal name appears to be Boy Scouts Association. To make clear that I am not referring to the USA’s Boy Scouts of America–also BSA–I prefix references to this Boy Scouts Association with “UK”. ↩︎

- “UK BSA” is a convenience initialization used in this article to differentiate the United Kingdom’s Boy Scouts Association from BSA, which stands for Boy Scouts of America. I do not believe the Boy Scout Association used that initialism. ↩︎

- Several, but not all, of Baden-Powell’s thoughts appear to be in response to a government proposal for dramatic expansion of the British Army’s cadets program for all boys. While he seems to be responding to proposal for boys roughly aged 15-18, he sometimes seems to refer to proposals that start at age 11. Baden-Powell saw the cadet program as inferior to Scouting, especially for the life stage of younger boys (11-14). ↩︎

- John Springhall, PhD, “Baden-Powell and the Scout Movement before 1920: Citizen Training or Soldiers of the Future?“, The English Historical Review, Oxford University Press, Oct., 1987, Vol. 102, No. 405, pp. 936-937 ↩︎

- “Founder–cadets, 1910-1916“, The Scout Association (UK), p. 18 and p. 170 ↩︎

- Ibid, p. 32 ↩︎

- Ibid, p. 75 ↩︎

- Ibid, p. 132 ↩︎

- B.-P.’s Outlook, The Scouter, “The Value of Camp Life”, April 1911 ↩︎

- Ibid, “Ridiculous Troops” October 1916. While in this case he was talking about elementary schoolers being in the same program as middle schoolers, the bigger-picture insight is how he conveyed the ridiculousness of combing two different life stages into the same program. ↩︎

- Ibid, “Retention of the Elder Scout, December 1916 ↩︎

- Baden-Powell was the Chief Scout and chairman for life in the fledging UK Boy Scouts Association. The foreword of Provisional Rules For Rover-Scouts is signed “THE CHIEF SCOUT”. Given these and Baden-Powell’s prior musings on separate sections for high schoolers, I am assuming much of this publication was written by him and that parts he did not write hewed closely to his values. ↩︎

- Scouting for Boys is the original handbook for the middle-school program. ↩︎

- Robert Baden-Powell, “ROVERS”, The Chief Scout Yarns, September 28, 1918. p. 4. (The linked publication is a compilation of a few years of these “Yarns” articles. The date and page number correspond only to the quoted article.) ↩︎

- A plain read of Rules for Rover Scouts may lead one to mistakenly believe Rovers were to act like an older-Scout patrol within a Scouts BSA troop. In fact, we are seeing early thoughts that evolved into the section model, which is employed in today’s The Scouting Association (the modern name for UK BSA) and by many of BSA’s peer Scouting organizations. In Rules for Rover Scouts book, “troop” relates somewhat to BSA’s concept of a chartered organization, in the sense that a CO may charter a pack, troop, and crew. The UK troop would have a Wolf Cubs section, a Scouts section, and a Rovers section. As Baden-Powell’s “Ridiculous Troops” article, cited earlier, warned against combining different life stages into one program, this further affirms that the language in Rules for Rover Scouts is properly understood as recommending program separation. ↩︎

- This conference, where a minimum age of 17 was set for Rovers, was a few months before the date on Provisional Rules for Rover-Scouts, which defined a program starting at age 15. I am not sure how to explain this. ↩︎

- Colin Walker, “Rover Scouts – Scouting for Men“, “Johnny” Walker’s Scouting Milestones ↩︎

- Robert Baden-Powell, Rovering to Success, p. 223, where it specifies that “members should be seventeen years of age or over on joining.” ↩︎

- This is mainly from a conversation I had with Colin Walker. However, while not explicitly stated here, this source supports the theory: “How Rovers Started“, Scouts History website ↩︎

- Robert Baden-Powell, Aids to Scoutmastership, 1919, p. 11. ↩︎

- Ibid, p. 16. ↩︎

- Ibid, p. 37-38. ↩︎

- “Ask your SPL” is how some adults diminish the adult-association part of Scouting, instead reinforcing to younger Scouts that they must accept being babysat by high schoolers. Literally, the adult denies the kid help, instead directing the kid to get help from a youth–typically a high schooler–in the Senior Patrol Leader role. In doing this, the adult leader also supports BSA’s undermining of the Patrol Leader role, which is intended to be the direct-contact leader for most troop youth. ↩︎

- Ibid, p. 15. ↩︎

- Senior and junior map approximately to today’s USA high-school and middle-school age cohorts. ↩︎

- Ibid, p. 15. ↩︎

- Tim Jeal, Baden-Powell, Yale University Press, 1989, p. 499 ↩︎

- “How Scouting grew“, UK Scouting Association. While this source asserts a 1946 start for the Senior Section, this might be apocryphal. I think there’s a chance that this is being confused with setting a maximum age for Rovers, which appears to have happened the same year. ↩︎

- Design for Scouting, The Chief Scout’s Advance Party Report, The Boy Scouts Association (UK), 1966. I believe that Explorers were implemented in 1967. ↩︎

- The leaving age for school at this time was 15, per Wikipedia‘s “Raising of school leaving age in England and Wales“. Therefore, it’s possible Venture Scouts’s age range was centered on a life stage marked by graduating from compulsory schooling. However, this in no way invalidates that today’s middle schoolers and high schoolers have considerable, natural differences in capability, outlook, and other crucial factors. I review this more later in this article. Also, be reminded that in the letters of Baden-Powell, from five decades earlier, in several cases identified separate age bands that correspond to middle school and high school. ↩︎

- I don’t know how to explain why this new program would cover ages 15.5-20, when 1946’s Senior Scouts covered 14-18. Did the Scouts aged 14-15.5 have to revert back to the middle-school program? I suspect, as per an earlier footnote, that the facts may be loose and that the late 1960s was the first time an older-youth section was created. ↩︎

- “Explorer Scouts“, Scouting Association website. ↩︎

- Official Handbook, Ernest Thompson Seton and Robert S.S. Baden-Powell, Boy Scouts of America, 1910, p. 4. ↩︎

- The joining age was 12 until 1949, when it switched to 11 (see Mark Ray, “Get With the Programs“, Scouting Magazine, January-February 2010). Today, one may join Scouts BSA as young as 10 years old, which affirms Seton’s younger end of his age bracket. ↩︎

- Ernest Thompson Seton, The Book of Woodcraft, Garden City Publishing Company, 1921, p. 6 ↩︎

- Context on Seton’s expulsion from BSA can be found in various sources. An example is William A. Farley, “Troops and Tribes: Masculinity, Playing Indian, and the Social Politics of Ernest Thompson Seton’s Expulsion from the Boy Scouts of America“, Connecticut History Review, October 2021. ↩︎

- Germany’s BdP and Denmark’s DDS place high schoolers and young adults in the same program. While that is not a recommendation of this article, their high schoolers are nevertheless in a different section than their middle schoolers. ↩︎

- While BSA’s Sea Scouts program is separate from Venturing, BSA often lumps Sea Scouts’s concerns with Venturing, often labeling the combined concern “Venturing”. This article follows BSA’s convention not out of hostility to Sea Scouts but, in many cases, due to a lack of differentiation in BSA’s own information. ↩︎

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; Board on Children, Youth, and Families; Committee on the Neurobiological and Socio-behavioral Science of Adolescent Development and Its Applications; Backes EP, Bonnie RJ, editors, “The Promise of Adolescence: Realizing Opportunity for All Youth“, National Academies Press (US), 2019 May 16. ↩︎

- John P. Cuhna, “What Are the Three Stages of Adolescence?“, eMedicineHealth (a publication of WebMD) ↩︎

- Frank Forest Bunker, The Junior High School Movement–Its Beginnings, 1935, pp. 24-25 ↩︎

- Howard E. Barbaree, and William L. Marshall, eds., The Juvenile Sex Offender, Guilford Publications, 2005, p. 20. The word use in this paragraph of the book is a bit jumbled, but the author appears to be referring to puberty as the kickoff to adolescence. It would be weird to say that puberty is a moment-in-time event that is followed by adolescence. ↩︎

- This statement is generally affirmed in research. Also, I have been a direct-contact leader for hundreds of youth over the past 15 years. I have observed considerable variance in onset of some secondary sex characteristics. Considering the most striking examples–youth whose onsets are before or after most their peers–the variance in my community is around six years. ↩︎

- This is inferred from how the educational system and virtually every formal activity for youth, like after-school clubs or church groups, provide different opportunities for high schoolers and middle-schoolers. Some may say sports is an exception, as younger kids can often “play up” on older teams. However, that is still a rolling window that blocks wide age differentials. The soccer team I coach has a four-year differential, the same maximum age differential as a typical high school. ↩︎

- Robert E. Frioni, Ed.D., “Caught in and left out of the middle: Where do ninth graders belong?“, LinkedIn, January 3, 2021. ↩︎

- Per Scouts BSA: Frequently Asked Questions (Boy Scouts of America) 10-year-olds may join Scouts BSA starting March 1 of their 5th grade year. ↩︎

- Cub Scouts often “cross over” to Scouts BSA months before their 5th grade year ends. The Scouts BSA program goes through the end of age 17, 12th graders are eligible to be in Scouts BSA. ↩︎

- In Types of Patrols, BSA recommends mixed-age patrols by listing it as the first option, without qualification. Therefore, it’s BSA’s recommendation that a 10 year old new member of Scouts BSA be in the same patrol as a 17 year old high-school senior. The patrol is the team that camps together, cooks together, and does all its activities together. Yes, this is super weird. ↩︎

- Patricia A Cavazos-Rehg, Melissa J Krauss, Edward L Spitznagel, Mario Schootman, Kathleen K Bucholz, Jeffrey F Peipert, Vetta Sanders-Thompson, Linda B Cottler, Laura Jean Bierut, “Age of sexual debut among US adolescents“, Contraception, April 23, 2009. Cited statistic came from a calculation on the numbers in table 1. In the “Age of first sexual intercourse” section, add up the precents for “11 years old or younger” though “17 years old or older”, then divide by the percent for “11 years old or younger” (3.24%). ↩︎

- Twenty-Ninth Annual Report of the Boy Scouts of America (1938), United States Government Printing Office, 1939, p. 300 ↩︎

- Ibid, p. 3 ↩︎

- Dr. Jay Mechling, On My Honor: Boy Scouts and the Making of American Youth, The University of Chicago Press, 2001. On p. 10, Dr. Mechling distinguishes the “Senior Patrol” as being a “patrol of boys aged fourteen to seventeen”. Given that this is a summer camp, all of these will be high schoolers. The other four patrols are of younger boys. This troop was long known as the BEST troop because B, E, S, and T are the first letters of the names of the four middle-school patrols. ↩︎

- Bryan Wendell, “This is how the average age of Eagle Scouts in 2017 compared to previous years“, Scouting Magazine, February 22, 2028. ↩︎

- This might be inferred by reviewing rank advancement, but that would be a loose estimate at best. ↩︎

- Handbook for Scoutmasters: A Manual of Leadership. Boy Scouts of America, 1932, p. 17. ↩︎

- While 14 is often cited as Venturing’s minimum age, 13-year-olds are allowed if they complete 8th grade. I once had a 9th grader who was 13 for most of his first year of Venturing. ↩︎

- The predecessor program, Exploring, includes units that focused on career-exploration. Such units were often associated with public entities, such as police departments, fire departments, and more. In 1998, reacting to increasing reluctance of public institutions to be associated with BSA’s bigotry regarding gays, girls, and God, BSA moved the career-emphasis part of Exploring, along with the Exploring brand, to its Learning for Life subsidiary, which lacked bigoted membership standards. The remainder of Exploring, which stayed under BSA and retained BSA’s bigoted membership policies, was renamed Venturing. ↩︎

- Michael R. Brown, “Exploring (1969-1998)“, A History of Senior Scouting Programs of the BSA. ↩︎

Leave a Reply