Boy Scouts of America (BSA) extensively promotes leadership development. On its home page, BSA’s “value of Scouting” statement concludes with “prepar[ing] youth for a lifetime of leadership.”1

While BSA instills valuable qualities in youth, an obsolete program design means few Scouts gain authentic leadership experience.

The Eagle Scout rank illustrates this. Nearly everyone who earns this rank does so while in the Scouts BSA program.2 Optimized for the developmental stage of middle schoolers, Scouts BSA does not emphasize leadership skills. Even the Eagle project3, while valuable, emphasizes administration and management.4 It doesn’t require key aspects of real leadership, like motivating a team over the long haul or driving a vision to completion beyond managing a checklist.5

We can fix this by recognizing what leadership is—and is not—and by improving BSA’s programs to offer more leadership development.

What leadership is

Leadership has three essentials:

- Defining a vision for change.

- Gaining voluntary buy-in to this vision.

- Fostering progress toward that vision with willing followers.

Importantly, these parts happen in a “mutual influence process independent of any formal role or hierarchical structure” (emphasis added).6

What leadership isn’t

Widespread misunderstandings cause us to label unrelated matters as “leadership”. This creates confusion and undermines leadership development.

BSA’s patrol method is not leadership

As implemented in Scouts BSA, the patrol method is not Baden-Powell’s the patrol method. In the 1950s, BSA departed from Baden-Powell’s vision, replacing it with a hierarchical bureaucracy. As a prescriptive system that features formal roles and clear lines of authority and emphasizes procedure, compliance, and supervision, BSA’s youth bureaucracy rests on administration, supervision, and management.

While little is black and white, the youth bureaucracy’s emphasis clear. Its strengths are in areas other than leadership.

Positive character attributes are not leadership

A common myth is that leadership is the same as positive character traits.

In a few social-media forums for adult leaders, I asked for people to share concepts they associate with leadership. All responses were great positive-character attributes:

These are positive character traits we’d want in anyone. Scouting does a great job of helping youth with these!

But we need to be careful about how we relate these traits to leadership. When we suggest exclusivity–that these are associated with leadership–what does that say about expectations of people in other roles? Incompetent administrators, unaccountable managers, immoral followers, unempathetic friends. That’s OK because they aren’t leaders?

Someone exhibiting these traits is showing good character! While that is to be celebrated, it is not related to whether that person is a leader.

Whether a person is a leader starts and ends with what is defined above: vision, gaining followers, then motivating followers towards achieving the vision. Positive character traits can help a leader’s effectiveness, but they alone are not leadership.

Babysitting is not leadership

Roughly 90% of BSA’s high schoolers remain in a middle-school program, Scouts BSA, mainly to supervise middle schoolers. This amounts to babysitting, and it is routinely confused with leadership. High schoolers’ babysitting chores include administrative duties, supervision, instruction, and make-work.

Often, older Scouts’ babysitting chores are under the color of “senior” troop roles of responsibility. As cogs in a bureaucratic scheme, these roles focus on management, checklists, authority, and procedures. The hallmarks of leadership–visions, voluntary buy-in, and willing followership–are largely absent in troops.

Administration or management talent is not leadership

Some claim that honing administrative or managerial ability produces leadership skill. That, too, is wrong.

A person can be an effective leader while having poor managerial, administrative, or supervisory skills. History and modern examples abound of effective leaders who needed skilled managers and administrators around them because the leaders lacked those gifts.

Likewise, one can be a great administrator but lack leadership ability. Such people can excel at operating systems.

Management, administration, and supervision are valuable in their own right. They can enhance a leader’s effectiveness. But they are not leadership. Leadership can exist without management, administration, and supervision, and mastery of these does not make someone a leader.

BSA’s youth bureaucracy is leadership with training wheels

A bicycle’s training wheels are a transitional support. You’re not really “riding a bike” until the training wheels come off.

The same applies to BSA’s youth-bureaucracy model. Like training wheels, this model is transitional support to ease future leadership development. You’re not engaged in leadership until after the troop’s training wheels come off.

The youth-bureaucracy model might be appropriate for middle schoolers’ developmental stage. Its structured environment helps Scouts grasp how to manage systems and exercise authority.

However, once youth are in high school, they are in a different developmental phase. They have marked changes in several developmental factors relevant to leadership, such as abstract thinking, emotional regulation, managing peer influence, navigating social relationships, and more. They are ready for authentic leadership experiences, so high school is the right time to rip off the troop’s training wheels.

This is where Venturing shines. Venturing crews operate with fewer formalities and less structure. Crews can shape their own organizational models, and older Scouts can lead peers rather than supervise younger children.

Leading one’s peers to accomplish bigger, more adventurous goals is a real challenge. This is more engaging and rewarding than keeping the younger Scouts in line.

Research shows that excessive reliance on training wheels can hinder learning to ride a bike.7 Holding high schoolers back in troops–keeping the middle-school training wheels on–obstructs leadership training!

How to fix this

The path to genuine leadership development within BSA is straightforward, but it requires moving beyond obsolete practices, leaving behind mistaken beliefs.

Most importantly, we must set side two myths about BSA’s babysitting regime.

Babysitting-regime myth 1: It’s essential to Scouting

A pervasive myth is that the babysitting regime was Robert Baden-Powell’s vision or that he saw it as essential to the patrol method or to Scouting.

Neither are true.

In the decade following his 1907 Brownsea Island experiment, Robert Baden-Powell wrote many letters citing major developmental differences between older and younger Scouts. He mulled on several ideas to improve Scouting for older Scouts. In 1918, Baden-Powell released his vision, where he recommended a separate section for an age band similar to today’s high schoolers. More detail is in the Baden-Powell got it section of Scouts BSA: a middle-school program unsuitable for high schoolers. (Ernest Thompson Seton, one of BSA’s founders, also got it!)

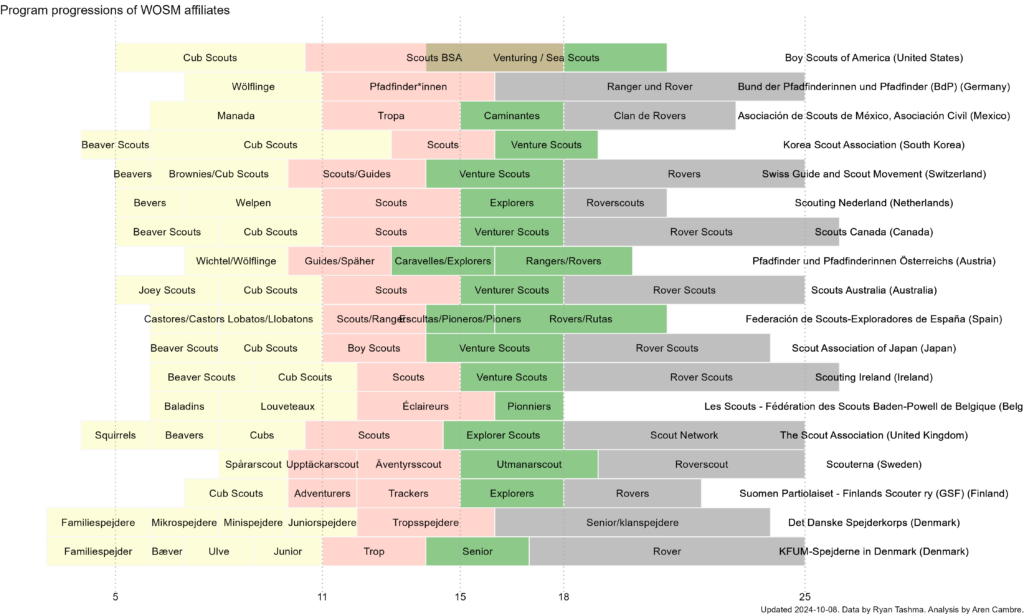

All of BSA’s international peer Scouting organizations have since realized Baden-Powell’s vision. None have babysitting regimes, instead providing separate, age-appropriate programming to age brands roughly equivalent to our high schoolers8:

It just takes cursory review of the UK Scouts section (again, only ages 11-14) to see a program that thrives without a babysitting regime. BSA, by contrast, is still stuck on an obsolete design from a century ago.

Babysitting-regime myth 2: It retains high schoolers

High schoolers have competition for their time and interest–other activities, romantic relationships, desire for more self-direction, increased academic load, and more. If serving high schoolers is important to BSA, it is crucial for BSA to value being attractive to high schoolers.

From day 1, both UK and USA Scouting programs observed that high schoolers found little appeal in their middle-school programs. For them, it was repetitious, more of the same stuff optimized for their younger selves. This is called the “older boy youth problem”.

For 115 years, BSA has run the same experiment again and again and again, theorizing that its babysitting regime can solve the “older youth problem”. That is, older youth will stick around if we give them the “reins” of a middle-school program.

Despite 115 years of trying, the babysitting regime never worked. The repetitive experiments always fail. Retention of high schoolers today remains as poor as always.

Babysitting-regime truth

We need to acknowledge truth about BSA’s babysitting regime:

- It’s not essential to Scotuing.

- It’s not part of the founder’s vision.

- It’s a failed experiment.

- It undermines leadership development for high schoolers.

With this improved understanding, we can review better approaches.

Start using words accurately

We must stop using “leadership” for orthogonal matters.

Stop using “leadership” to describe BSA’s youth bureaucracy. It is not leadership.

Stop using “leadership” to describe generic, positive character attributes. They are not leadership.

Stop using “leadership” to describe administration or management. Neither are leadership.

Stop using “leadership” to describe babysitting chores. Supervision is not leadership.

Only use leadership to describe a visionary, voluntary, mutual influence process separate from formal roles or hierarchy.

Accept where leadership is not emphasized

Adolescence is a period of rapid changes, where various cognitive and emotional abilities generally “turn on” at certain phases. One’s capacity to be a leader largely rests on abilities that generally “turn on” during high school (middle adolescence), such as abstract thought. Younger children and early adolescents are typically not ready for intense leadership development.10 That is normal.

They can still learn skills, confidence, and positive-character traits. This is valuable!

But a program optimized for middle schoolers is speaking to a different life stage than high schoolers. To support leadership development in age-appropriate ways, different approaches are needed for middle schoolers and high schoolers.

Begin to value high schoolers

BSA must finally align itself with its peer Scouting organizations worldwide, the USA educational system, and virtually all major youth-serving USA organizations. It must end its babysitting regime, instead providing older youth with genuinely age-appropriate programs.

BSA should move all high schoolers into Venturing. This already exists, is high quality, and is designed around the life stage that high schoolers are in. Venturing is tragically underused.

I acknowledge that some troops cluster older Scouts, allowing them a degree of independence. While this goes the right direction, it’s only baby steps. These high schoolers remain peers to middle schoolers, infantilized in a program optimized for middle schoolers. Also, these arrangements generally maintain a strong expectation of participation in the babysitting regime. When that new crop of 5th graders crosses over in the spring, we know who’s going to–sigh–yet again repeat the annual cycle of teaching Tenderfoot skills.

I also acknowledge that BSA has other opportunities that appeal to high schoolers trapped in the middle-school program, like high adventure and camp staff. These are not a solution to the babysitting regime. While valuable, these opportunities are feasible for few high schoolers. Also, once the opportunity is done, the high schooler just returns to the babysitting regime. (Some would add Order of the Arrow to this list. Neck deep in racism, OA is a stain on Scouting. It must be abolished, and its high-school programming needs to be liberated to Venturing.)

Transition from units to groups with sections

To avoid fragmentation, BSA should adopt the group and section model, which our international peers generally use.

In this model, all units at a given location–a pack, troop, and crew at one chartered organization–would be merged into one group with sections for each former unit. The group has one committee, one pool of adult leaders, and one pool of equipment.

The group’s key-three adult leaders would be a group-level program leader, Committee Chair, and Chartered Organization Representative. Each section would still have its own program lead (Cubmaster, Scoutmaster, Advisor, etc.).

While each section must provide separate, age-appropriate programming, limited cross-section coordination can ease logistical challenges and promote collaboration.

Reassess BSA’s implementation of the patrol method

Program improvements for high schoolers also provide opportunities for major improvements to the middle-school program.

We should reassess BSA’s interpretation of the patrol method. BSA’s model is not Baden-Powell’s model!

BSA’s model often reduces the Patrol Leaders (PL) to an intermediary between the troop’s youth and the Senior Patrol Leader (SPL). Typically, PLs just implement concrete orders of the SPL.11

We should adjust the patrol method to allow more genuine leadership for the middle schoolers who are ready.

The UK Scouting Association can be an inspiration. In Robert Baden-Powell’s Brownsea Island experiment, there was no SPL. In the UK Scouts section today (ages 11-14), the SPL role is optional, often unused.12

In that style, each patrol leader takes initiative in coordinating activities or collaborating with other patrol leaders. For example, a troop of 30 Scouts might be split into four patrols that operate semi-independently. Each Patrol Leader coordinates activities and even inter-patrol competitions or service projects, with adult leaders mentoring. An SPL, if present, is often just the most senior Patrol Leader, mainly coordinating between patrols.

This offers more authentic leadership-development opportunity for middle-schoolers while still providing appropriate structure and age-appropriate programming.

Create Guides position of responsibility

Serving younger cohorts is valuable for those who are willing and able.

When I was a Den Leader, Cameron was my Den Chief for over three years. A high schooler, he did a fantastic job helping me with the den. I appreciated him so much.

As a youth soccer coach, I take a collection from parents so that I can pay talented older youth to help train the team. Paul, Malcolm, Ellie, Andrea, Merrick, and Ben have all been highly appreciated, providing valuable training to the team members.

Replacing Den Chief, Troop Guide, and Junior Assistant Scoutmaster will be a new Guide role.

The Guide is a new position of responsibility, where a youth member, in any program, serves a younger program by mentoring youth to success or assisting adults. The younger youth do not report to or take orders from a Guide. Instead, the Guide builds up younger youth in the style of servant leadership13.

The Guide may manage activities episodically, when requested by an adult leader, such as supervising a hike when the Patrol Leader lacks that capability.

Attachment to the babysitting regime will be strong, so guardrails are needed. The Guide role may not displace age-appropriate programming. Also, the Guide role must be voluntary. A Scout must never be coerced into a Guide role, and no unit may be coerced into supplying Guides to any other unit.

For example, it would be inappropriate to have a Venturing crew that has all its members be Guides for a troop and has no significant program beyond its members’ service to that troop. That is perpetuation of the babysitting regime.

Strengthen First Class and Eagle Scout ranks, abolish paper Eagles

Moving all high schoolers into an age-appropriate program is an opportunity to strengthen the rank system.

Today’s Eagle Scout rank is diminished by being the last rank in a woodcraft-centric, middle-school badge progression. It is possible to earn Eagle Scout at a young age–as young as 12 years old14–leading to a “paper Eagle” problem. Also, the 17-year-old senior earning Eagle Scout depends on steps that youth took starting in 5th grade. That is absurd.

We aren’t shooting high enough, and we aren’t doing it right. Eagle Scout should be strengthened as the terminal of a rank program one starts in high school. It should signify distinctive life skills, character development, and true leadership experience that sets the recipient apart from high-school peers.

We can also strengthen the First Class rank. Today, it’s diminished, lost as an intermediate badge in BSA’s middle-school badge program.

Becoming the terminal rank of the Scouts BSA program, we can strengthen First Class to meet Robert Baden-Powell’s original vision, where it signified when the Scout “really get[s] the value of the Scout training” and is “ground[ed] in the qualities, mental, moral, and physical, that go to make a good useful man.”15

A strengthened First Class rank will emphasize:

- Mastery. Instead of being busywork one knocks out rapidly, the Trail to First Class is a series of steps that we take with a decided interest in mastery.

- Adventure. Trail to First Class becomes a prescription for adventure. Instead of the requirements being “random things I have to do at the next campout”, they induce and enhance adventures. This can be helped with a three-year rolling suggested itinerary for troops.

- Authentic. With a three-year path to First Class, we reduce advancement pressure, opening more opportunity for an authentic Scouting experience.

The new pace of advancement will help Scouts BSA be more comfortable for Scouts who are today uninterested in advancement. For some, an increase focus on adventure provides such Scouts more room to find meaningful experiences. For others, recasting advancement as a prescription for adventure makes it so that earning advancement feels more like a natural outcome of active participation.

With this, First Class also becomes a distinction worthy of celebration.

- www.scouting.org, Boy Scouts of America. ↩︎

- I estimate that over 90% of high schoolers in BSA remain in Scouts BSA, the middle-school program. Even for those who are involved in BSA’s high-school program, Venturing, while Eagle Scout may be competed in Venturing, it appears common for Venturers seeking Eagle to dual-register in the middle-school program and complete Eagle there. ↩︎

- Simply calling it a “project” distances the Eagle project from leadership. Project management is grounded in management and administration, not leadership. In “The Leap from Project Manager to CEO Is Hard — But Not Impossible” (Harvard Business Review, November 8, 2023), Antonio Nieto-Rodriguez uses the “Gantt ceiling” to illustrate how successful project managers must also develop leadership capability–again, a different domain than project management–to be a contender for a leadership role. ↩︎

- To wit, the Eagle Scout Service Project Workbook–a requirement to do an Eagle project–is a detailed, 32-page form. ↩︎

- The Guide to Advancement purports to define leadership expectations for Eagle projects in section 9.0.2.4 (p. 67), titled “Give Leadership to Others …”. In fact, this section of Guide declines to clarify any leadership expectations! Instead, the authors reveal widespread confusion between management and leadership, evident by prohibitions on the use of management concerns to evaluate leadership. For example, an Eagle project’s success may not hinge on the number of people managed, total hours worked, or whether project participants met a performance standard. While these “nos” have value, BSA declines to clearly state what leadership means. ↩︎

- D. Scott DeRue, Susan J. Ashford, “Who Will Lead and Who Will Follow? A Social Process of Leadership Identity Construction in Organizations“, Academy of Management, October 2010. ↩︎

- Various studies are cited and summarized in the Limitations section of Wikipedia’s Training wheels article. ↩︎

- These age bands do not line up exactly; the correlation is approximate. There are historical or societal reasons why they may not, such as differences in how secondary education is construed. ↩︎

- While Denmark and Germany combine high school and early adulthood into one program–they lack a green band–that is not recommended for BSA. The broader point is that at roughly USA high-school ages, the Scout graduates from the middle-school program. ↩︎

- I used “often” because I have experienced some exceptions with older middle schoolers (ages 13-14) who appear surprisingly ready for serious leadership development. ↩︎

- Some counter that BSA’s youth bureaucracy empowers Patrol Leaders. In practice, BSA’s youth bureaucracy, and its hierarchical structure, undermines Patrol Leaders, reducing them to carrying out concrete orders. Also, youth naturally gravitate to simpler, more black-and-white solutions, thus leaning toward administration rather than genuine leadership. ↩︎

- While there is an option for an SPL in the UK’s Scouts section, there’s mixed used of the role. Often, the role is not used. When it is, the role is reserved for an older Scouts section member–13 or 14–or it’s occupied by an Explorer section member (14-18) who’s voluntarily in a Youth Leadership Scheme (around a tenth of Explorers do that scheme). ↩︎

- Conventional notions of leadership describe an informal change process that affects institutions or systems. Servant leadership is still an informal change process, but instead of affecting an institution or system, the end result is development or enablement of a person. ↩︎

- The critical path to get Eagle is 18 months: 1 month (Second Class requirement 7a) + 1 month (First Class requirement 8a) + 4 months (Star requirements 1 and 5) + 6 months (Life requirements 1 and 4) + 6 months (Eagle Scout requirements 1 and 4). Someone who joins a troop at age 10.5 can complete Eagle Scout not long after a 12th birthday. ↩︎

- Robert Baden-Powell, “B.-P.’s Outlook: First-class Scout”, The Scouter, February 1914. ↩︎

Leave a Reply